Viktoria Mullova (violin), Alasdair Beatson (fortepiano). Signum SIGCD706.

By Bill Heck

When I happened upon this recording, my ears immediately perked up: I had happily and favorably reviewed a disc of Beethoven sonatas performed by these same musicians (see https://classicalcandor.blogspot.com/2021/07/beethoven-violin-sonatas-4-5-and-7-cd.html), and so was eager to hear what they were up to with Schubert. Would they live up to that same high standard? Read on…

The works on this album are the Violin Sonata In A Major, D. 574 (Op. 162), apparently composed in 1817; the Fantasie In C Major, D. 934 (Op.159) from December of 1827; and the Rondo In B Minor, D. 895 (Op. 70) from late 1826. As many readers will know, Schubert composed at a furious rate, leaving many hundreds of works at his death in 1828 at just 31 years of age. Appreciation for his work was limited to small numbers of musically knowledgeable Viennese at the time of his death, but his works were quickly rediscovered and promoted by leading composers including Mendelssohn, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, and more. I need hardly add that Schubert now is regarded as one of the supreme composers of the late classical to early romantic period – or of any other period.

Keeping track of all of his works, many (most?) of which were unpublished in his lifetime, is a gargantuan task. And difficult as that might be, just imagine keeping track of all the recordings of those many works. Which brings up the question: what night make the current album stand out?

Well, there’s the obvious point regarding the musicianship of the two performers. Moreover, unlike many earlier recordings of these works, these are “historically informed performances” (HIPs, and yes, that’s the real acronym), and indeed are played on period instruments. A period violin is nothing unusual, but Mullova’s instrument is strung with gut, which makes for a different sound than modern strings. Beatson plays a copy of a fortepiano from 1809, which most certainly has a different sound than a modern piano.

Now let's start with positives. The first word that comes to my mind in regard to the performances is “passionate", especially Mullova's playing, with the word "sprightly" not far behind. The performances, especially that of the early Sonata, make the music interesting and engaging, as it well should be. There is considerable dynamic range, something that does not always happen with some HIPs. However, I don't feel that this duo lives up to the standard set in the album that I mentioned above.

First, in regard to the playing, there are a few mannerisms that I find bothersome. For example, in some transitions between phrases where the fortepiano is alone, Beatson seems to rush the notes and, on occasion, not sound the last note or two quite clearly; listen, for instance, at about 1:00 and 2:15 in the first movement. A minor issue, but it does tend to interrupt the flow.

But my larger concerns have to do, in a broad sense, with the recorded sound. Unlike the Beethoven recording on the Onyx label, this one, on Signum, is in a much more reverberant environment. That acoustic “scene,” and perhaps the recording technique, emphasize what I hear as the clanginess and, if I can use the term, the “slowness” of the forte piano, to the point at which I am reminded of the sound of a piano in saloon scenes in old westerns. Moreover, the two instruments are placed oddly: the fortepiano seems to be far back in a more reverberant space than the violin, a discontinuity that I find disconcerting. Also, and particularly in the Sonata, when Mullova is playing more loudly, it sounds as though she is leaning into the microphone, which creates an unnatural increase in volume.

Compare all this to another fine recording of the Sonata by Manze and Egarr on Harmonia Mundi. This one also is an HIP and was recorded in a very reverberant space as well. While again the fortepiano has that same clangy quality, and even sounds a little congested in the lower registers, the spirit and dynamics make it through more clearly.

Similarly, in the Fantasie, it sounds as though the music is trying to escape the confines of the fortepiano. Is the recording the issue? Is Beatson's playing too stolid? Is the fortepiano insufficiently responsive? I don't know, but for me the music simply is not taking off. In contrast, in the excellent recording by Tomas Cotik and Tao Lin on Centaur--admittedly not on period instruments--the music sings; it clearly belongs to the romantic period.

No doubt there are others who will hear the fine playing on this album--and despite my reservations, there’s plenty of it--and think that I’m completely off base. But if you can give up the HIP angle, give a listen to the same works on the Cotik / Lin album and see what you think. Or if you really are looking for an HIP version, check out the Manze and Egarr album of Violin Sonatas, including the A Major.

BH

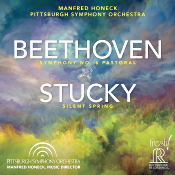

Also, Stucky: Silent Spring. Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Reference Recordings FR-7475SACD.

By John J. Puccio

Beethoven wrote nine symphonies, at least five of which (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9) are probably the best known and most popular. But if I had to guess further, I’d say that today’s average non-classical music listener might only know the first four notes of the Fifth and the finale of the Ninth (oh, yeah, they’d say, that’s from Die-Hard). Yet thanks in part to Disney’s Fantasia, they might also recognize most any part of the Sixth. Which brings us to a dilemma faced by any conductor undertaking a new recording of the “Pastoral”: how to make it different enough to distinguish it from the 800 other recordings currently available and make it worthwhile enough for potential buyers to consider adding it to their music library.

Face it: There are already some great recordings of the Sixth Symphony from distinguished conductors like Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Karl Bohm, Otto Klemperer, Eugene Jochum, Jordi Savall, and many others. What would set Manfred Honeck’s rendition with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra apart from the rest? Well, certainly, Maestro Honeck chose a symphony with as great a variety of interpretations as any in the catalogue.

First, of course, there’s the matter Honeck discusses in the booklet notes. Should one approach the “Pastoral” as program or absolute, abstract music? He reasons that Beethoven gave us enough explanation of each movement that it is inevitable the composer meant for us to picture in our minds the scenes and events he’s describing. Honeck goes on to say, however, that there is a good deal of feeling in the music, Beethoven indicting in the score that the music should be played with “more sensation than painting.” So, one must not overlook the nuances of the score and create more than simply a cursory overview of the image. Honeck goes on in his extraordinarily thorough booklet notes to identify the various passages that he felt needed further clarification through extended contrasts or an emphasis on certain instruments.

Then there is the matter of tempos. Ah, yes, those tempos. Beethoven, it seems, fell in love with the newfangled metronome and added detailed tempo markings throughout his music. This was not to the liking of every conductor, as they preferred the broader Latin markings of Allegro, Andante, Largo, etc., which gave them more leeway in adopting a pace they preferred. An actual, specific tempo many of them felt was too restrictive. What’s more, just as many musical scholars believed (and some still believe) that Beethoven’s metronome may have been faulty because the speeds are so much more uniformly fast that most conductors were used to. Whatever, with the popular introduction of historically informed performance practice (HIP) and the period-instrument era of the mid-twentieth century, the adoption of Beethoven’s own tempo markings became more widespread. Ensembles like Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players, John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, and Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations among others helped put Beethoven’s own tempo markings back on the map. Still, these were period-instrument bands, and Honeck leads a modern-instrument one. Would he follow traditional big-orchestral practice or adopt Beethovent’s markings? It appears Honeck chose Beethoven. His timings for each of the Sixth Symphony’s movements are consistently as fast or even faster than Norrington, Gardiner, or Savall and clearly faster than most modern-orchestra recordings.

So, how does all of this work out for Maestro Honeck and the listener? That may depend of what you’re looking for in the work and, especially, what you’re used to. Let’s take the recording one movement at a time.

The first movement Beethoven marks as an Allegro ma non troppo (fast but not too fast) and calls it the “Arrival in the country.” Well, Honeck certainly got the “fast” part right, but the “not too fast” seems to elude him. Fortunately, the wide dynamcs and the dramatic pauses help to make the music vigorous and noteworthy. But I’m not sure an arrival in the country should be this hurried, despite the composer’s tempo marks.

The second movement is the “Scene at the brook,” marked Andante molto mosso (moderately fast). Traditionally, this would actually be a “slow” movement, but following Beethoven’s lead, Honeck again takes it rather briskly. Still, Honeck’s brook bubbles away in perfect harmony with Nature, and it appears as though the company of people at the stream are enjoying themselves.

The third movement Beethoven called the “Merry assembly of country folk” and labeled it an Allegro. Here, Honeck is clearly in his element. “It is said the peasants are revolting.” “You said it! They stink on ice!” --Mel Brooks, History of the World, Part I. The country folk do, indeed, appear to be having a good time.

The fifth movement, the “Thunderstorm,” Beethoven also labeled an Allegro. The storm is undoubtedly noisy, with the recording’s wide dynamics practically knocking you out of your chair. Honeck clearly achieves the impact the composer probably desired.

Then, the final movement is the “Shepherd's Song,” with the additional description “Benevolent feelings of thanksgiving to the deity after the storm.” Beethoven tags it an Allegretto (moderately fast but not so fast as an Allegro). Because the indicated tempos are significantly different from those we usually hear from modern orchestras, Honeck’s approach doesn’t seem fully to capture the merrymakers’ gratitude to the Lord at the passing of the thunder and lightning. It doesn’t project the exalted serenity we normally hear.

Now, whether my several qualms are justified, given Beethoven’s own intentions, or whether I am basing them on personal expectations due to years of listening to more conventional performances, I’m not sure. I do know that, for instance, I disliked Roger Norrington’s HIP approach of the Sixth, finding it rather antiseptic, but found Jordi Savall’s equally HIP approach totally delightful. All I can say about Honeck’s interpretation is that it may be a matter of acquired taste.

Coupled with the Beethoven is Steven Stucky’s Silent Spring, commissioned by and premiered in 2012 by Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Mr. Stucky (1949-2016) wrote his four-movement composition as a tribute to Rachel Carson’s best-selling 1962 wake-up call for environmentalism. Taking Carson’s own titles for the four movements, Stucky’s music reflects the themes of the book: “The Sea Around Us,” “The Lost Woods,” “Rivers of Death,” and “Silent Spring.” Honeck and the orchestra would seem to reflect these moods perfectly, and Stucky’s tone poem comes over as a wake-up call of its own.

Producer Dirk Sobotka and engineer Mark Donahue recorded the music live at Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts in June 2017 (Symphony No. 6) and April 2018 (Silent Spring). They recorded it for SACD 5.0 and 2-channel stereo playback as well as regular CD stereo, using five omnidirectional DPA 4006 microphones as the main array, supplemented by “spot mics” to clarify the detail of the orchestration. The recording itself was made in DSD256 and post-produced in DXD 352.8kHz/32 bit. I listened in SACD two-channel.

For a live recording, the sound of the Sixth is remarkably lifelike, meaning it’s not as close-up, bright, or one one-dimensional as are most live recordings. If anything, it’s a touch soft. Miked at a moderate distance, it sounds big and full, warm and natural. The wide dynamics help it seem even more realistic, although some listeners may object to the abrupt changes in playback levels. I enjoyed it. The sound of Silent Spring is more hi-fi oriented, a tad sharper and clearer and in-your-face.

JJP

Puts: Contact; Higdon: Concerto 4-3. Time for Three (Charles Yang, violin; Nick Kendall, violin; Ranaan Meyer, double bass), Xian Zhang, The Philadelphia Orchestra. Deutsche Grammophon B0035748-02.

By Karl W. Nehring

This album came to me as a combination of the known (composer Jennifer Higdon and The Philadelphia Orchestra) and the unknown (composer Kevin Puts, conductor Xian Zhang, and the performers known collectively as Time for Three). Having never heard anything by Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962) that I didn’t like, and having great admiration for the venerable Philadelphia Orchestra, I felt reasonably confident that this release was going to be worth listening to, although I really did have no idea what kinds of sounds might emanate from my speakers the first time I hit the play button on the remote.

Much to my surprise, the first few notes of Contact by American composer Kevin Puts (b. 1972) were not instrumental, but vocal. Puts, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2017 for his first opera, Silent Night, explains in the liner notes that “Contact, a concerto in four movements, begins with Time for Three singing a wordless refrain. The piece’s four movements – ‘The Call,’ ‘Codes, ‘Contact,’ and ‘Convivium’ – tell a story that I hope transcends abstract musical expression. Could the refrain at the opening of the concerto be a message from Earth, sent into space? Could the Morse-code-like rhythms of the scherzo suggest radio transmissions, wave signals, etc.? The word ‘contact’ has gained new resonance during these years of isolation, and it is my hope that our concerto will be heard as an expression of earning for this fundamental human need.” As I listened to the piece over multiple sessions, I discovered that the concerto gives the musicians of Time for Three plenty of opportunity to display their musicianship, whether it be fancy fiddling as in the energetic first movement or the middle Eastern sounding melodies of the final movement, where Time for Three also add to the mood with some more wordless singing during the final minute. The orchestra provides solid support throughout, especially so in the third movement, Contact, a haunting and mysterious slow movement, the longest of the four, wherein the Philadelphia woodwinds and brass provide washes of color that enhance the splendor of the sound. The seamless transition to the energy of the final movement is simply remarkable, while the ending of the concerto demonstrates that Puts apparently knows how to end a composition just right – neither making it suddenly become overly dramatic nor letting it simply die out. Yep, just right.

Fellow American composer Jennifer Higdon is also a Pulitzer Prize winner, having been awarded that honor in 2010 for her Violin Concerto, the same year she was awarded a Grammy for her Percussion Concerto. She has since gone on to collect two more Grammy awards, in 2018 for her Viola Concerto and in 2020 for her Harp Concerto. (Hmmm, I seem to detect a pattern here. It looks as though a concerto from Ms. Higdon might be a pretty safe bet…) As I mentioned above, I have listened to a number of releases of her music, and always enjoyed them. As our own John Puccio noted of her music in his review of one of her earlier compositions, “ Unlike so many late twentieth-century composers, Ms. Higdon believes in writing real tunes, melodies, rather than simply inventing new soundscapes.”

Of her approach to her new Concerto 4-3, Higdon writes, “I knew the Time for Three Guys before we had the chance to work together; we crossed paths at Curtis, where I taught, and I often heard them jamming in Rittenhouse Square. When I got the call from the Philadelphia Orchestra to write them a concerto, I was thrilled and knew exactly what to compose: a work that would show off the joy that they express in their music. Concerto 4-3 is a three-movement concerto with an optional cadenza between the first and second movements. Each movement title refers to rivers that run through the Smoky Mountains: ‘The Shallows,’ ‘Little River,’ and ‘Roaring Smokies.’ The concerto embraces a traditionally classical approach with elements of bluegrass being incorporated into the fabric of the piece. All occurring within a tonal, 21st Century American style.” Although I hardly expect to hear Tim White introducing Time for Three on “Song of the Mountains” anytime soon to play this concerto, you really can hear little threads of bluegrass that are woven into the piece here and there. What you can really hear, though, is energy and enthusiasm, both in the playing and even in the music itself, which at times truly does seem to evoke the whirling and swirling and bubbling motion of rivers as their waters wend their way determinedly downstream. There are also passages of great tenderness, such as the vocalization near the end of the first movement that leads into the lyrical instrumental passages with which the second movement begins.

Engineer Adam Abeshouse has done an excellent job of balancing the sound so that the solo instruments stand out but never seem larger than life. Throughout both concertos your ears are most likely first to be captured by the sound of the two violins, but as you listen more, you may well begin also to appreciate the contributions of the double bass – at times being plucked, sounding like a jazz bass, at other times being bowed, producing more of a singing quality, and more often than not making a significant contribution to the music even though notes from the double bass do not have the penetrating power that those from the violins possess. From the opening measures of the Puts through the closing measures of the Higdon, Letters for the Future is an engaging release that demonstrates that serious, high-quality, contemporary classical music can be highly entertaining, accessible, and enjoyable.

KWN

Music of Albeniz, Chopin, Debussy, Liszt, Schubert, and Schumann. Daniel Barenboim, piano. DG 486 0932.

By John J. Puccio

By now, Daniel Barenboim’s name is undoubtedly familiar to almost every classical music fan far and wide. He came to my attention in the late 1960’s when I was becoming ever more serious about listening to and collecting classical music. He was among a handful of pianists whom I admired, among them Maurizo Pollini, Van Cliburn, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and Martha Argerich, which was pretty heady company.

Barenboim (b. 1942) is, of course, both a pianist and a conductor; a citizen of Argentina, Israel, Spain, and Palestine; the current Music Director of the Berlin State Opera and the Staatskapelle Berlin; and the former conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, and La Scala. With his numerous recordings as both a pianist and conductor, it’s no wonder his name is so well known.

For the present solo piano album, he offers us a bit of respite from the hectic world in which we all live, some “encores” as he calls them. They are charming, well-known piano miniatures from some of the most well-known composers of the classical world, pieces he has often used as encores in his stage recitals. Here’s a rundown of the program:

Schubert: Impromptu in G flat

Schubert: Moment musical in F minor

Schumann: Traumerei

Schumann: Fantasiestucke, Op. 12

Schumann: Aufschwung. Warum? Traumes Wirren

Liszt: Consolation No. 3 in D flat

Chopin: Nocturne in F sharp major

Chopin: 3 Etudes, Op. 25, Nos. 1, 2 and 7

Chopin: 3 Etudes, Op. 10, Nos. 4, 6 and 8

Debussy: Clair de lune

Albeniz: Tango from Espana

As Barenboim remarks, these miniatures may be brief, but they are long on significance. They are packed with emotion, feeling, and atmosphere. The first two of the selections are from Franz Schubert, who practically invented the use of “songs without words.” It’s good to see that Barenboim hasn’t lost his touch when it comes to projecting a comfortably relaxed interpretation. This is especially true, too, of Robert Schumann’s lovely Traumerei (“Dreaming,” the seventh of Schumann’s thirteen Scenes from Childhood). Barenboim maintains the music’s serenity without giving in to sentimentality.

And so it goes with all of the selections. Each displays Barenboim’s subtlety and grace, his assured manner, and sensitive technique. Liszt’s Consolation No. 3 evokes a stillness and comfort; Chopin’s Nocturne No. 3 a dreamy ease; the Etudes a sweet, gentle purity contrasted with a lively spirit. Debussy’s Clair de lune comes in the penultimate spot, fitting for a major little masterpiece. Needless to say, Barenboim plays it with all due respect, a glowing, towering little gem. Then the pianist ends the show with one of my favorite tangos, No. 2 from Espana. It provides a fitting conclusion to an album of refinement, eloquence, and intellect.

Producer Friedemann Engelbrecht and engineer Julian Schwenkner recorded the music at Pierre Boulez Saal, Berlin in April 2020 and Teldex Studio Berlin in 2017. DG always do a good job recording piano music, and this is no exception. The piano tone is warmer and mellower than usual, but it’s still realistic, reminiscent of a piano playing in a large room, with plenty of rich resonance. Transparency is fine, and the instrument appears to be rather closely miked, so that adds to the detailing.

JJP

Max Richter, Moog synthesizer; Elena Urioste, solo violin; Chineke! Orchestra. Deutsche Grammophon 4862769.

By Karl W. Nehring

Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons has long been a favorite of classical music fans, often serving as the gateway drug that hooks innocent young ears on the genre. From Vivaldi to Mozart to Beethoven and before long, the unthinkable – they find themselves addicted to Mahler, or in extreme cases, they might even find themselves frantically seeking out alternative editions of Bruckner symphonies. For Vivaldi fans old and new, there are countless recordings of the piece available, including the recent version by I Musici recently reviewed by John J. Puccio: https://classicalcandor.blogspot.com/2022/05/vivaldi-le-quattro-stagioni-cd-review.html. If you take a look at John’s review, you will note that I Musici themselves have recorded the work several times over the years, but they are certainly not the only recognizable musical name to have had more than one go at recording Vivaldi’s greatest hit. Still, it was surprising to learn that composer Max Richter (b. 1966) has now released the second recording of his “recomposed” version of Vivaldi’s masterpiece. The first release, titled Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi, The Four Seasons, featured Daniel Hope on solo violin with the Kammerorchester Berlin under conductor André de Ridder along with Richter on electronic synthesizers. It was initially released by Deutsche Grammophon in the summer of 2012 and then later rereleased in 2014 in an expanded version that was also reviewed in Classical Candor by John Puccio: https://classicalcandor.blogspot.com/2014/04/recomposed-by-max-richter-cd-review.html

Now, a decade later, we have another recomposition of the score by Richter, this time around one of the main differences being that not only do we have (other than Richter) different musicians, but they are playing different sorts of instruments. According to the liner notes, both the Chineke! Orchestra (a British ensemble consisting primarily of Black, Asian, and other ethnically diverse musicians) plus violin soloist Elena Elena Urioste “are playing on gut strings and period instruments: the sort that Vivaldi would have heard, and played in his own time.” Richter says of this new version that “I don’t see this as a replacement, but it is another way of looking at the material. It’s like shining a light through something from a fresh angle. There’s a romance about that, as if a layer of dust has been blown off… I love the slight grittiness and earthy feeling that gut strings have. I wanted to match that flinty, haptic, tactile texture with the electronic elements.”

In keeping with the “early instruments” theme, it turns out this time around, Richter did not avail himself of the latest sorts of electronic instruments, but rather played his synthesizer parts on an early Moog dating from the 1970s. Moreover, the recording was mixed not digitally, as you might well take for granted these days, but rather on an analog mixer. Richter explains that “those [Moogs] are the first-generation synths…They have a certain presence and authority about them. I mean, they are crude in a way, but they are also like someone inventing the wheel. They have gravitas.” Indeed, the synthesizer does add weight and yes, gravitas to the proceedings, as Richter uses it at times to add bass underpinnings that of course Vivaldi would never have imagined but which add a foundation to the sonic structure that sounds entirely natural and appropriate. Although the idea of a synthesizer might strike fear into the minds of some potential listeners, rest assured that Richter does not use the Moog in such a way as to call attention to itself. Instead, the sound of the Moog fits right in with the rest of the ensemble. I mentioned the occasional use of the Moog to provide a bass foundation to the sound, but another welcome way that Richter employs the Moog is by making it sound like a harpsichord – an instrument that always adds charm to the sound of the Seasons. And speaking of sound, the sonics of this release are superb, with solidity and quite believable imaging. The engineering team (Rupert Coulson, recording engineer and mixing; Alice Bennett, recordist and editing; Götz-Michael Rieth, mastering) did a remarkable job on this one. Kudos to the whole team!

So… what have we here? This is certainly not just another recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. Vivaldi’s venerable compostion, so familiar and so beloved to so many, truly has been “recomposed.” However, it has not lost its essential character. Richter’s version is clearly a version that is faithful to Vivaldi’s vision. If you enjoy the energy, drive, color, and variety of Vivaldi’s original, you will very likely get quite a kick out of Richter’s 2022 recomposed version, which has energy, drive, color, and variety in abundance, and is appropriately well-performed and well-recorded to boot. What a hoot!

KWN

Chen Reiss, soprano; Semyon Bychkov, Czech Philharmonic. Pentatone PTC 5186 972.

By John J. Puccio

During his career Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) wrote nine symphonies. Or ten if you count his final, unfinished symphony. Or eleven if you count his unnumbered symphony Das Lied von der Erde (“The Song of the Earth”). Whatever, judging by the number of recordings available, Nos. 1 and 4 are among the most popular. They are also his shortest symphonies and some of his most accessible, which could account for their allure, and this is disregarding the unfavorable reception No. 4 had upon its premiere in 1901.

With dozens of Mahler Fourth Symphony recordings currently accessible, it may seem odd that Russian conductor Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic would choose to give us yet another one. Still, given the number of new recordings we get every year of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Bach’s Brandenburgs, Pachelbel’s Canon, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, and Rachmaninov’s piano concertos, one can understand the appeal of surefire classics to sell.

So, can Bychkov’s version stand up to competing performances from the likes of George Szell (HDTT or Sony), Bernard Haitink (Philips), Fritz Reiner (RCA or RCA/JVC), Otto Klemperer (EMI), James Levine (RCA), Simon Rattle (EMI), Herbert von Karajan (DG), Colin Davis (RCA), and so many more? And is this new recording just for classical beginners, those just starting a classical collection, or will it please those classical fans who already have established favorites on their shelves?

As you probably know, Mahler intended at least his first four symphonies as extensions of one another, one following another in a kind of symbolic progression. In the First Symphony the composer describes, musically, Man’s suffering and triumph. In the Second he examines death and resurrection. In the Third he reflects upon his own existence and that of God. And one of his disciples, the conductor Bruno Walter, described the Fourth as “a joyous dream of happiness and of eternal life promises him, and us also, that we have been saved."

More specifically, the first movement, which Mahler marks as "gay, deliberate, and leisurely," begins playfully, with the jingling of sleigh bells. The second movement introduces Death into the picture, with a vaguely sinister violin motif. The slow, third-movement Adagio, marked "peacefully," is a kind of reprieve from the mysteries of Mr. Death in the previous section. Then, in the fourth and final movement, we get Mahler's vision of heaven and salvation as exemplified in the simple innocence of an old Bavarian folk song, a part of the German folk-poem collection Das Knaben Wunderhorn that Mahler loved. Here, the composer wanted the song to sound so unaffected that he insisted upon the soprano's part being sung with "child-like bright expression, always without parody."

Now, how does Maestro Bychkov handle all of this? Well, about as well as anyone and in some regards, like sensitivity, perhaps a touch better. Most of the performance seemed rather ordinary to me; good ordinary, mind you. As in something you would expect from a first-class conductor. The first movement, for instance, builds upon the simple sleigh bells into something almost monumental, and Bychkov handles these transitions with a deliberate calm, conveying the music’s spirit through the score rather than any added theatrics of his own. And why the Czech Philharmonic, by the way? We should remember that Mahler was born and raised in what is now a part of the Czech Republic; that the Czech Philharmonic is a tremendously talented ensemble, which actually premiered Mahler’s later Seventh Symphony; and that Semyon Bychkov just happens to be the Chief Conductor and Music Director of the orchestra.

Bychkov might have taken the second movement a bit more colorfully, though. It doesn’t convey quite the sinister charm I had hoped for. Bychkov approaches it rather carefully, rather leisurely, not quite communicating its full potential for eccentricity. In the slow third-movement Adagio Bychkov is, indeed, slow; slower than I think I can recall from any other conductor. But it is lovely in the extreme; just long. Then, in the finale, Bychkov has Chen Reiss as his soprano. She does project Mahler’s prescribed “child-like innocence,” which is to the good, but Bychkov seems intent on undermining it at points with a relentless forward drive. Still, it all holds up pretty well, and on the whole Bychkov’s is a satisfying rendering of the symphony. But I would never consider it a substitute for the Szell, Haitink, Reiner, Klemperer, Rattle, Levine, Karajan, or Davis recordings I mentioned at the start.

Producers Robert Hanc, Renaud Loranger, and Holger Urbach and engineers Stephan Reh and Jakub Hadraba recorded the music at the Dvorak Hall of the Rudolfinum, Prague, Czech Republic in August 2020. Pentatone made this one is two-channel stereo, so there’s no SACD multichannel involved. Regardless, it’s quite good, with a natural frequency balance and a realistic acoustic setting. Left-to-right balance is also lifelike, with a moderate degree of depth and dimensionality. The dynamic range seems adequate for the job, although there are no moments of spectacle, no overly strong punches. It’s just solid, modern sound.

JJP

Works by Florence Price, Valerie Coleman, and Jessie Montgomery. Price: Ethiopia’s Shadow in America; Coleman: Umoja: Anthem of Unity for orchestra; Price: Piano Concerto in One Movement; Montgomery: Soul Force. Michelle Cann, piano; Michael Repper, New York Youth Symphony. AVIE AV2503.

This is a remarkable recording for at least three reasons that jump immediately to mind. First, of course, is the music. Not long ago, Florence Price would have been considered an unknown composer, but over the past year or two (pretty much coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, curiously and morbidly enough) her music has begun to attract attention and there have been some excellent recordings of some of her compositions recently, a couple of which I reviewed here: https://classicalcandor.blogspot.com/2022/04/recent-releases-no-27-cd-reviews.html,

On this new release, there are two pieces by Price, but there also two much more recent compositions by two living composers, Valerie Coleman (b. 1970) and Jessie Montgomery (b. 1981).

The next reason is the orchestra, a remarkable group of young musicians. The New York Youth Symphony was founded in 1963 not only to provide opportunities for young musicians but also to bring music to the greater New York community and provide a vehicle for composers to get their compositions played. According to the liner notes: “Though its First Music program, NYYS has commissioned and premiered over 100 works by American composers and received 15 ASCAP awards for Adventuresome Programming.” Of course we should also recognize their conductor, Michael Repper, who has led them since 2017 and sees as his mission to use music as a vehicle for positive change within communities, and the piano soloist, Michelle Cann, who has been a champion of the music of Florence Price.

Finally, there is the way the recording was made, which was not typical of an orchestral recording. It was recorded in November 2020, as the grim reality of COVID-19 was beginning to really sink in. The musicians and engineers were bound and determined to make this recording, but at the same time, equally bound and determined to do so as safely as possible. That meant that the sessions simply could not be conducted as they normally would, with the orchestra assembled together in the same space. Following social distancing guidelines, it just wasn’t going to work. As a result, they devised a plan to record the album in pieces, so to speak, with different section of the orchestra recording their parts at different times, playing against a “click track,” and then mixing down the various tracks into the final master from which the CD was produced. There is a brief video available on YouTube that offers an overview of the process: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8ZzMfFBOa8&t=183s

The recording was produced by the industry veteran Judith Sherman, who also had a hand in the engineering, editing, and mixing. Over her career she has been nominated for a Grammy 17 times, winning 12 of them, most recently earlier in 2022 for Classical Music Producer of the Year. The recording team (Isaiah Abolin, lead recording engineer; Neal Shaw, Teng Chen, Joe Cilento, assistant engineers; Jeanne Velonis, production assistant; Sherman, John Kilgore, Velonis, editing; Kilgore, Sherman, Repper, editing; Sherman, Velonis, mastering) did a highly believable job of assembling a convincing whole from the separate parts. Bill Heck and I have had several discussion about how contemporary digital recording technology offers such a powerful, flexible tool for capturing the sound of musical performance when wielded by engineers who really know what they are doing, which is clearly the case here.

The excellent engineering is evident early in the program as we are treated to a bit of Telarc-style bass in the colorful opening measures of Florence Price’s Ethiopia’s Shadow in America. Despite the recording have been made by mixing multiple tracks together, the background is dead silent. As the piece continues, various sections of the orchestra get their turn to shine, with exuberant phrases being tossed back and forth from woodwinds to strings, then to brass, with percussion also given their chance to join in the fun. If you’ve not heard this piece before, you are in for a treat. Next up is Umoja (Swahili for “Unity”) by Valerie Coleman (b. 1971), which was originally composed as a song for women’s choir, later rearranged for wind quintet, and now rearranged once again for orchestra as presented here. From the mysterious opening, with its sense of “space music,” the music seems to unfold itself into something grand and very American-sounding, heroic in its sweep and vision. Although Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement is so titled, there really can be heard three distinct movements or sections, it’s just that they are played without pause. The piece opens with trumpet, then the piano, with the music taking on a wistful, longing feeling. The second movement is lyrical and melodic, while the third movement is infused with rhythmic energy. The more I listen to this composition, the more I begin to think that it might be my favorite of Price’s works. The program closes with Soul Force by Jessie Montgomery (b. 1981), a work in one movement that according to the composer “attempts to portray the notion of a voice that struggles to be heard beyond the shackles of oppression… Drawing on elements of popular African-American musical styles such as big-band jazz, funk, hip-hop and R+B, the piece pays homage to the cultural contributions, the many voices, which have risen against aggressive forces to create an indispensable cultural place. I have drawn the work’s title from Dr. Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in which he states: ‘We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.’” The music starts with percussion, then brass, with strings and winds getting their turn as the music unfolds. For all its syncopated energy – and there is plenty – the music is remarkable in never losing its dignity.

Dr. Samantha Ege of Oxford University, a leading scholar of the music of Florence Price who is also a concert pianist who has played and recorded some of Price’s music has contributed some brief liner notes. Combined with the excellent engineering and interesting program (not just another recording of Beethoven symphonies – as much as we all love Beethoven, it is always nice to have something new and different), it all adds up to a new release that is well worth seeking out for a good listen.

KWN

Music of Corelli, Bach, Paganini, and more. Anne Akiko Meyers, violin; Jason Vieaux, guitar; Fabio Bidini, piano. Avie AV2455.

By John J. Puccio

American concert violinist Anne Akiko Meyers has always seemed to me to produce some of the most graceful, most sensitive music in the classical world. That has never been more noticeable than in her latest album, “Shining Night.” Here’s a rundown of the contents to illustrate the point:

Arcangelo Corelli: La Folia

J.S. Bach: Air on G

Niccolo Paganini: Cantabile

Manuel Ponce: Estrellita “Little Star”

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Aria from Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5

Duke Ellington: “In My Solitude”

Astor Piazzolla: “Bordel” 1900, “Cafe” 1930, “Night-club” 1960, “Concert d’aujourd’hui”

Hugo Peretti: “Can’t Help Falling Love”

Leo Brouwer: Laude al Arbol Gigante

Morten Lauridsen: “Dirait-On” and “Sure on This Shining Night”

Ms. Meyers describes her motivation for the album coming from a conversation she had with composer Morten Lauridsen, whom she asked if he had written any duos that included the violin. He said he had written a tune describing a man going on a walk and thinking back over his life. She then says, “That inspired this collection of pieces that metaphorically begins in the morning and explores the vast musical history through Baroque, Romantic, Popular, and current genres. The common themes throughout the music reflect on one’s relationship with nature, love, and poetry. And how in dark and challenging times, kindness profoundly affects our souls and opens infinite possibilities when living our lives.”

So, she begins the program with Corelli’s La Folia, written some 400 years ago, and continues through Lauridsen’s relatively recent “Sure on This Shining Night.” Ms. Meyers does full justice to each of the pieces, from the regal elegance of Corelli to the more modern material. In fact, the Corelli becomes wonderfully vibrant in places, alternating with Meyers’s effectively contemplative interludes. The “Folio” was a popular dance of the day that followed a series of diverse variations, all of which Ms. Meyers conveys with equal ease.

The familiar “Air” from Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 never sounded more beautiful, taken neither too fast nor too slow. As with most of the selections on the album, Ms. Meyers makes the music sing. It’s quite lovely, especially when she follows it up with Paganini’s equally lyrical Contabile. Jason Vieaux’s gently sympathetic guitar accompaniment adds to the sweetness of the affair.

We reach the twentieth century with the music of Gerald Ponce, his quiet Estrellita “Little Star” leading the way. It’s a romantic song reflecting the sorrow, pain, and hope of love. Ms. Meyers follows that with an ode to the moon by Villa-Lobos, all shadowy twilight and, again, her violin voices the notes as a singer might, with tenderness and understanding. The music is poignant and evocative; the playing is exquisite. Put another way, the album’s sixty-seven minutes seemed far shorter and for me could have gone on forever.

And so it goes. If you love the sound of the violin in the hands of expert technician and artisan of her trade, you can’t do much better than Anne Akiko Meyers. As I said in the beginning, her artistry is always skilled, delicate, intricate, and touching. She makes every note mean something as few musicians can. In the present album, we hear her at her best and most eloquent.

Producers David Frost and Anne Akiko Meyers and engineers Silas Brown and Sergey Parfenov recorded the music at Zipper Hall at the Colburn School in November 2021. The violin tone is luscious, clean, clear, never edgy or bright, and the guitar and piano accompaniments are moderately recessed to give proper dominance to the violin.

JJP

David Starobin. Bridge Records Bridge 9567.

By Bill Heck

This is getting to be a habit: several of my recent reviews have explored lesser-known corners of classical music, finding interesting and delightful works in unexpected places. (I apologize to the dedicated and knowledgeable musicians for whom the corners are well-known, and the places expected, but I believe that I speak for many readers here.) Well, not to bury the lede: here we go again.

Wenzeslaus Thomas Matiegka is hardly a household name today, but in the burgeoning classical music scene of early 19th century Vienna, it certainly was. Born in rural Bohemia (then part of the Hapsburg empire) in 1773, he moved to Vienna, the city of Beethoven and Schubert in 1800, starting as a piano teacher. Matiegka quickly adopted a new instrument and blossomed into one of the city’s most influential composers for guitar – this at the time of a guitar craze in the city.

Multiple musical threads and trends were coming together in Vienna in the early part of the century, say 1800 – 1830: the influence of Beethoven, and before him Mozart, is obvious, but there were plenty of other composers, including names such as Mauro Giuliani and Anton Diabelli – yes, the Diabelli of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. (And there was Schubert, but sadly he was little known to the public at the time.) But in addition to Vienna’s status as a hotbed of compositional talent, music publishing as an industry was really getting rolling, and musical instruments were evolving into the forms that we see today.

On the guitar front specifically, I quote from a private communication from my friend, John Finn: Multi-movement sonatas are very important in 19the century guitar music literature. There are not many, and they are the jewels of the repertoire. Giuliani, Carulli, and Sor wrote both single movement (single pieces in sonata allegro form, or sinfonia) and multi-movement sonatas (complete with an allegro in sonata form and one to three following movements, following the pattern of Hadyn and Mozart). These composers were inventing “classical” guitar to make the instrument relevant to the art culture of their time. This was vital for these musicians because the physical guitar had just evolved (in the late 18th century) from the five-course [string] guitar of the late Baroque to the six-string “modern” guitar we all know and love. Matiegka was among these inventors.

The public may sometimes associate “classical guitar” solely with Spanish composers and musical traditions. While it is true that many Spanish and Latin American composers have written for the guitar, and that there have been superb guitarists from both regions, the works here demonstrate that the instrument also drew the attention of musicians across Europe and beyond, with both compositional and performing practices based on the broad traditions of western classical music.

Fascinating as this background is – and we have barely skimmed the surface – it is time to move on to the album itself, which gives us six of the Matiegka’s twelve published sonatas. Once I settled in to listen, my reaction to the first piece was that it was competent, workmanlike, historically interesting – but for modern ears, what was all the excitement about? The second sonata came along, bringing some more interest, but it was in the third sonata where the music truly came to life: harmonically more adventuresome, rhythmically complex. By the end of number six, I felt as though I had taken a metaphorical musical tour of courtly proceedings, country festivals, and outbursts of song and dance, with both good fun and a dose of imaginative counterpoint along the way, capped with a visit to the coming land of full-blown Romanticism. Were these all really by the same composer?

A clue to the nature of the progression is provided by the sequence of keys: C natural, then its relative minor (A minor), then G major….ending in D major and B minor. Matiegka was a teacher, after all, not to mention a working stiff who needed to sell his compositions, so perhaps he was presenting works to be played – not necessarily by beginning students but rather by intermediate and up performers – that increase in difficulty and, not coincidentally, in musical interest. A second clue is on title page of the score: Six Sonatas Progressives pour Guitare: Matiegka clearly meant these works to be more challenging as one went along. While most listeners will not care about the pedagogical or financial issues, they should be aware that, musically speaking, things get better…and much better…and still better as you go along.

As to the performances, readers of Classical Candor who may not have heard of Matiegka are more likely to have heard of David Starobin, a well-known and very influential classical guitarist with multiple Grammy nominations and various awards to his credit. Recently retired from the concert circuit, Starobin has not left the musical world; he remains active with teaching and writing and as head of Bridge Records.

In these works, Starobin’s playing is excellent. I would call it expressive but straightforward, not in the sense of uninvolved or uninteresting, but in the sense of playing the music as it was written without imposing odd or idiosyncratic effects. By the time we reach the later sonatas, the difficulty level has become significant, e.g., handling the dotted rhythms in the later sonatas or maintaining the multiple voices in the Scherzo of number 6, but Starobin sails through with no difficulty. The detailed and informative liner notes are by Paul Cesarczyk, who provides extensive background about Matiegka and musical Vienna. Finally, the sound of the guitar is well-represented, with natural-sounding reverberation from the hall (perhaps a church?) but not so much as to obscure the music.

Competition? There’s not much: a quick search turned up a total of four CDs or CD sets mainly featuring Matiegka’s music for guitar. Among these, the only other way to get all the Op 31 sonatas is on the Brilliant Classics complete works set (not evaluated here). Given the quality of Starobin’s playing, the excellence of the Bridge recording, and the quality of the music itself, the current disk would be worthwhile addition to the library of any classical guitar fan – or any lover of early Romantic music. My only “complaint” is that this album is rumored to be Starobin’s last, that he has retired not only from public but also from recorded performance. Might we persuade him to provide us with one more helping of Matiegka in some future project?

Special thanks to John Finn, an accomplished amateur guitarist and one far more knowledgeable than I about the goings-on for guitar in Matiegka’s time. John provided much of the information used in this review.

BH

John J. Puccio, Founder and Contributor

Understand, I'm just an everyday guy reacting to something I love. And I've been doing it for a very long time, my appreciation for classical music starting with the musical excerpts on the Big Jon and Sparkie radio show in the early Fifties and the purchase of my first recording, The 101 Strings Play the Classics, around 1956. In the late Sixties I began teaching high school English and Film Studies as well as becoming interested in hi-fi, my audio ambitions graduating me from a pair of AR-3 speakers to the Fulton J's recommended by The Stereophile's J. Gordon Holt. In the early Seventies, I began writing for a number of audio magazines, including Audio Excellence, Audio Forum, The Boston Audio Society Speaker, The American Record Guide, and from 1976 until 2008, The $ensible Sound, for which I served as Classical Music Editor.

Today, I'm retired from teaching and use a pair of bi-amped VMPS RM40s loudspeakers for my listening. In addition to writing for the Classical Candor blog, I served as the Movie Review Editor for the Web site Movie Metropolis (formerly DVDTown) from 1997-2013. Music and movies. Life couldn't be better.

Karl Nehring, Editor and Contributor

For nearly 30 years I was the editor of The $ensible Sound magazine and a regular contributor to both its equipment and recordings review pages. I would not presume to present myself as some sort of expert on music, but I have a deep love for and appreciation of many types of music, "classical" especially, and have listened to thousands of recordings over the years, many of which still line the walls of my listening room (and occasionally spill onto the furniture and floor, much to the chagrin of my long-suffering wife). I have always taken the approach as a reviewer that what I am trying to do is simply to point out to readers that I have come across a recording that I have found of interest, a recording that I think they might appreciate my having pointed out to them. I suppose that sounds a bit simple-minded, but I know I appreciate reading reviews by others that do the same for me — point out recordings that they think I might enjoy.

For readers who might be wondering about what kind of system I am using to do my listening, I should probably point out that I do a LOT of music listening and employ a variety of means to do so in a variety of environments, as I would imagine many music lovers also do. Starting at the more grandiose end of the scale, the system in which I do my most serious listening comprises Marantz CD 6007 and Onkyo CD 7030 CD players, NAD C 658 streaming preamp/DAC, Legacy Audio PowerBloc2 amplifier, and a pair of Legacy Audio Focus SE loudspeakers. I occasionally do some listening through pair of Sennheiser 560S headphones. I miss the excellent ELS Studio sound system in our 2016 Acura RDX (now my wife's daily driver) on which I had ripped more than a hundred favorite CDs to the hard drive, so now when driving my 2024 Honda CRV Sport L Hybrid, I stream music from my phone through its adequate but hardly outstanding factory system. For more casual listening at home when I am not in my listening room, I often stream music through a Roku Streambar Pro system (soundbar plus four surround speakers and a 10" sealed subwoofer) that has surprisingly nice sound for such a diminutive physical presence and reasonable price. Finally, at the least grandiose end of the scale, I have an Ultimate Ears Wonderboom II Bluetooth speaker and a pair of Google Pro Earbuds for those occasions where I am somewhere by myself without a sound system but in desperate need of a musical fix. I just can’t imagine life without music and I am humbly grateful for the technologies that enable us to enjoy it in so many wonderful ways.

William (Bill) Heck, Webmaster and Contributor

Among my early childhood memories are those of listening to my mother playing records (some even 78 rpm ones!) of both classical music and jazz tunes. I suppose that her love of music was transmitted genetically, and my interest was sustained by years of playing in rock bands – until I realized that this was no way to make a living. The interest in classical music was rekindled in grad school when the university FM station serving as background music for studying happened to play the Brahms First Symphony. As the work came to an end, it struck me forcibly that this was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard, and from that point on, I never looked back. This revelation was to the detriment of my studies, as I subsequently spent way too much time simply listening, but music has remained a significant part of my life. These days, although I still can tell a trumpet from a bassoon and a quarter note from a treble clef, I have to admit that I remain a nonexpert. But I do love music in general and classical music in particular, and I enjoy sharing both information and opinions about it.

The audiophile bug bit about the same time that I returned to classical music. I’ve gone through plenty of equipment, brands from Audio Research to Yamaha, and the best of it has opened new audio insights. Along the way, I reviewed components, and occasionally recordings, for The $ensible Sound magazine. Most recently I’ve moved to my “ultimate system” consisting of a BlueSound Node streamer, an ancient Toshiba multi-format disk player serving as a CD transport, Legacy Wavelet II DAC/preamp/crossover, dual Legacy PowerBloc2 amps, and Legacy Signature SE speakers (biamped), all connected with decently made, no-frills cables. With the arrival of CD and higher resolution streaming, that is now the source for most of my listening.

Ryan Ross, Contributor

I started listening to and studying classical music in earnest nearly three decades ago. This interest grew naturally out of my training as a pianist. I am now a musicologist by profession, specializing in British and other symphonic music of the 19th and 20th centuries. My scholarly work has been published in major music journals, as well as in other outlets. Current research focuses include twentieth-century symphonic historiography, and the music of Jean Sibelius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Malcolm Arnold.

I am honored to contribute writings to Classical Candor. In an age where the classical recording industry is being subjected to such profound pressures and changes, it is more important than ever for those of us steeped in this cultural tradition to continue to foster its love and exposure. I hope that my readers can find value, no matter how modest, in what I offer here.

Bryan Geyer, Technical Analyst

I initially embraced classical music in 1954 when I mistuned my car radio and heard the Heifetz recording of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto. That inspired me to board the new "hi-fi" DIY bandwagon. In 1957 I joined one of the pioneer semiconductor makers and spent the next 32 years marketing transistors and microcircuits to military contractors. Home audio DIY projects remained a personal passion until 1989 when we created our own new photography equipment company. I later (2012) revived my interest in two channel audio when we "downsized" our life and determined that mini-monitors + paired subwoofers were a great way to mate fine music with the space constraints of condo living.

Visitors that view my technical papers on this site may wonder why they appear here, rather than on a site that features audio equipment reviews. My reason is that I tried the latter, and prefer to publish for people who actually want to listen to music; not to equipment. My focus is in describing what's technically beneficial to assure that the sound of the system will accurately replicate the source input signal (i. e. exhibit high accuracy) without inordinate cost and complexity. Conversely, most of the audiophiles of today strive to achieve sound that's euphonic, i.e. be personally satisfying. In essence, audiophiles seek sound that's consistent with their desire; the music is simply a test signal.

Mission Statement

It is the goal of Classical Candor to promote the enjoyment of classical music. Other forms of music come and go--minuets, waltzes, ragtime, blues, jazz, bebop, country-western, rock-'n'-roll, heavy metal, rap, and the rest--but classical music has been around for hundreds of years and will continue to be around for hundreds more. It's no accident that every major city in the world has one or more symphony orchestras.

When I was young, I heard it said that only intellectuals could appreciate classical music, that it required dedicated concentration to appreciate. Nonsense. I'm no intellectual, and I've always loved classical music. Anyone who's ever seen and enjoyed Disney's Fantasia or a Looney Tunes cartoon playing Rossini's William Tell Overture or Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 can attest to the power and joy of classical music, and that's just about everybody.

So, if Classical Candor can expand one's awareness of classical music and bring more joy to one's life, more power to it. It's done its job. --John J. Puccio

Contact Information

Readers with polite, courteous, helpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@gmail.com

Readers with impolite, discourteous, bitchy, whining, complaining, nasty, mean-spirited, unhelpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@recycle.bin.