by Bill Heck

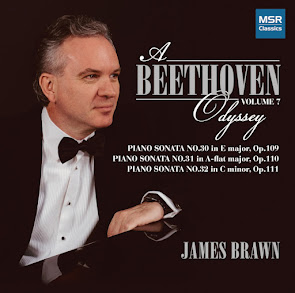

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 30, 31, and 32. James

Brawn, piano. MSR Classics MS 1471

The release of a volume in pianist James Brawn's wandering traversal of the Beethoven piano sonatas certainly calls for a review, if not for downright celebration, here at Classical Candor. Our esteemed founder, John Puccio, reviewed several earlier volumes quite favorably; indeed, Brawn's series of discs is one of the three listed as “Recommended Recordings” on this website. Although I was a bit late to the party, not knowing of Brawn’s work until a few years ago, I have joined him in admiration of the series.

| |

| Brawn: A Beethoven Odyssey, Vol 7 |

I mentioned that we have two volumes, with number 7 being the one reviewed here. I’ll post a review of number 8 shortly. Meanwhile, my colleague Karl Nehring will add a few comments at the end of this review.

Given the infinite possibilities of these works, and given that almost every pianist of any repute whatsoever has had a go at them, it would be inane to speak of the “best” versions out there. What I can do here is to recommend the latest installments in this series as versions that you really should hear, and to tell you why I will return to them often myself. (One amusing digression: I asked ChatGPT to write a brief review of this album, and it produced a highly readable account with some interesting details. Unfortunately, it thought that Sonata 25 was included in this volume – it’s not – and, while correctly including number 30, missed the presence of numbers 31 and 32. I try to approach these reviews with a sense of my own limitations, and that’s especially true with such a revered part of the repertoire as the late sonatas, but apparently I’m still more qualified for this effort than AI!)

If you are unfamiliar with the work of pianist James Brawn, check out John’s aforementioned reviews of Volume 2, Volume 4, Volume 5, and Volume 6. In these reviews, he consistently praises Brawn’s playing, and as I agree wholeheartedly with his sentiments, allow me to share a few quotes here. “…an interpretation…carefully planned around the composer's wishes, so while it is clearly Brawn's reading, it remains Beethoven's music” and “his playing is thoughtful and purposeful as well as thoroughly entertaining.”, and the obligatory mention of technical capability “…pianistic virtuosity that is quite dazzling.” One analogy in particular grabbed my attention: “…when you've got a favorite actor or actress in a part, and you can't imagine anyone else doing it better…? …other people could have done justice…but you doubt that anyone else could have improved upon them. That's the way I feel about…James Brawn and his performances.”

I’ll also repeat a sentiment that John stresses: paise for Brawn’s work takes nothing away from other fine performances. It's just that Brawn's work always feels consistently "right”.

Back to my own words: Brawn’s interpretations not only sound right in total; within each piece the choices that he makes – changes (or not) of tempo, slight emphasis on particular notes or lines to bring them forward (or the opposite), and so on – all sound organically correct, parameters necessitated by the overall conception of the work. In other words, the music flows forth and carries you along with the feeling that all is exactly as it should be.

There’s another dimension, though, that is the “secret superpower” of this series, and that is the superb, natural recorded sound. Consider just the other two series on our Recommended Recordings list, those by Wilhelm Kempff and Alfred Brendel. While I yield to no one in my admiration for Kempff's work, his final sonata series was made in the early 1960s. While good for its time, the recording does not have the body, range, and clarity of a current digital recording. Similarly, Brendel's series was done later, but still does not have the weight of a contemporary recording. I certainly don't want to say that either set is unlistenable; hey, even the old Schnabel recordings let the music through in a way that can be appreciated. But the MSR recording team, headed by producer Jeremy Hayes and engineer Ben Connellan, capture a startlingly natural and dynamic sound, bringing the music seemingly right in front of you, particularly in the often troublesome areas of the deeper bass registers and the high treble notes of the piano. Don’t underestimate the power of a first-rate recording to help the music come alive and to allow you to immerse yourself in it, especially if you have invested in a quality sound system.

| |

| Beethoven |

Number 30 was dedicated to Maximiliane Brentano, the daughter of Antonie, who in turn likely was the “immortal beloved” of whom Beethoven wrote elsewhere. Indeed, this work abounds in moments of extraordinary beauty and a sense of longing, expressed quite wonderfully here, but in the end the profound musicality of Beethoven takes over in the third and final movement with a series of six variations. In this recording, we have both the emotion and the power. By the way, here’s an example of both Brawn’s touch as a pianist and the engineering prowess of the MSR team: In the huge climactic cascade of notes at 11: 50 in the last movement, the very highest notes of the piano, which in a lesser recording might be clangy or edgy, float ethereally over the raucous goings on of the left hand. The result is magical.

Number 31 was written as Beethoven was beginning to recover from a serious illness. The first movement is, as mentioned earlier, almost of a continuation of the final movement of number 30. Personally, I think of it as a backward looking celebration of life, with uncertainty mixed in – but that may be carrying a programmatic view a little too far! In any case, the second movement slyly refers to two humorous popular songs of Beethoven's time. (Beethoven’s Austro-German contemporaries would have gotten the joke; it was rediscovered for us rather recently.) As I listen to Brawn’s playing, I hear the humor but also a certain wistfulness, an emotion that we've all experienced, especially those of us who are a little older: the entertaining moment before our thoughts return to the more serious side of life, that side that we never really forgot even as we laughed. The third and final movement gradually builds, perhaps to celebrate recovery from illness and the triumph of returning health; Beethoven’s own letters indicate that he is happy to be able to work hard again at his art. The playing is what I might call quietly expressive, meaning that Brawn manages to convey the deep emotional content within the context of logical development. In particular, the solidity of the lower registers is contrasted in a lovely way with the fluidity of the upper voice of the central fugue.

On my first quick listen to this performance of Number 32, I was confused, perhaps disappointed; the music wasn’t registering with me. Had Brawn finally missed one? Well, no, and I should have known: I had not heard this amazing work in a some time, and a "quick listen" was bound to disappoint. But as I listened again, both to his recording and to several other superb ones, the music, radical as it is, crept into my mind on its own terms. As that happened, I again heard that sense of “rightness” that Brawn so often brings. This is a lovely performance: perhaps initially seeming understated (and slower than, say, Kovakevich’s early 2000’s effort), but in the end tremendously satisfying.

One interesting note: much of the second (final) movement is in a meter common in jazz. But in jazz, the players who really swing do so by microscopically adjusting the timing, “dragging” some the notes. (If you’ve ever played swing, you know what I mean.) But as I hear it, Brawn seems to “unswing” it. I have no idea whether he was trying to do that, but it alters what the music might otherwise sound like to our modern ears in a way that makes it easier to hear what Beethoven, by this time completely deaf, must have heard in his mind.

Karl Nehring’s Take

John Puccio had good things to say about earlier installments in this set of Beethoven sonatas by James Brawn, so when I was offered the chance to audition Brawn’s recording of the Beethoven’s three final sonatas, I could not pass it up. To my mind, the late piano sonatas of Beethoven and Schubert stand in a class by themselves, magnificent works of art that never fail to evoke fresh wonder and delight in my mind no matter how many times I listen to them. My first listens to the Brawn release were under casual circumstances and my first impressions were favorable; he sounded smooth, expressive, perhaps a bit soft-edged. When I finally got a chance to audition the CD on my main system, my favorable impressions were confirmed. Brawn indeed plays expressively, his interpretation enhanced by the excellent engineering, which puts a bit more distance between listener and piano than is often the case, but without veering toward the overly resonant sound that shows up from time to time on some recordings. I must say that I am impressed by this new release, and not just for its sonic attributes. This will stay on my shelf right next to Uchida; believe me, that is high praise indeed. Her playing is a bit more forceful at times, while the engineering is more forward without being excessively so. Both pianists obviously love the music and serve it well, as do their respective engineers; moreover, this new release on MSR exhibits some of the very finest recorded piano sound I have ever encountered. This is without question a highly recommendable release.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment. It will be published after review.