By Karl W. Nehring

Bach | Sei Solo | Kavakos. Bach: Sonatas & Partitas for Solo Violin Nos. 1-3. Leonidas Kavakos, violin. Sony Classics 19439983132.

Beethoven for Three. Beethoven: Symphony No 2 in D major, op. 36 (arrangement for piano trio attributed to Ferdinand Ries, under the supervision of the composer); Symphony No. 5 in C minor, op. 67 (arrangement for piano trio by Colin Matthews). Emanuel Ax, piano; Leonidas Kavakos, violin; Yo-Yo Ma, cello. Sony Classical 19439940142.

Weinberg: Sonatas for Violin Solo. Gidon Kremer, violin. ECM New Series 2705.

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7. Gianandrea Noseda, London Symphony Orchestra. LSO Live LSO0859.

KWN

Music by Freitas Branco, Ravel, Villa-Lobos. Bruno Monteiro, violin; Joao Paulo Santos, Piano. Et’cetera Records KTC 1750.

By John J. Puccio

Let us begin with a refresher on the participants, Bruno Monteiro, violin, and Joao Paulo Santos, piano. According to his biography, Mr. Monteiro is "heralded by the daily Publico as one of Portugal’s premier violinists” and by the weekly Expresso as “one of today's most renowned Portuguese musicians.” He is internationally recognized as an eminent violinist, whom Fanfare describes as having a “burnished golden tone” and Strad says has “a generous vibrato” producing radiant colors. Music Web International refers to his interpretations as having a “vitality and an imagination that are looking unequivocally to the future” and that reach an “almost ideal balance between the expressive and the intellectual.” Gramophone lauds his “unfailing assurance and eloquence” and Strings Magazine notes that he is “a young chamber musician of extraordinary sensitivity."

Monteiro’s accompanist, the Spanish pianist Joao Paulo Santos, is a graduate of the Lisbon National Conservatory, completing his piano studies in Paris with Aldo Ciccolini. For the past forty years he has worked with the Lisbon Opera House, first as Chief Chorus Conductor and more recently as Director of Musical and Stage Studies. He has also distinguished himself as an opera conductor, a concert pianist, and a researcher. Together, Monteiro and Santos make an outstanding team and make outstanding music.

On the present album, they offer three sonatas for violin and piano. The first, by Luis De Freitas Branco (1890-1955), perhaps the least well known of the composers represented on the program. De Freitas was a Portuguese composer, professor, and musicologist who played an important role in the evolution of Portuguese music in the first half of the twentieth century. Among his most-important works are four symphonies, a violin concerto, and any number of shorter pieces, including the selection we have here, the Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano, written in 1908 when the composer was only seventeen years old and a conservatory student in Lisbon. It created a bit of stir in the musical world because of its somewhat revolutionary (i.e., modern) tendencies. Let’s say, its cyclical form and occasional dissonances were not as easy on the ears as most of its Romantic predecessors.

The opening movement is an Andantino, a little faster than an Andante, which itself can be fairly slow. Whatever, the Andantino is the closest thing in the sonata to being in the purely Romantic vein, at least the way Monteiro and Santos play it. It is sweet and lyrical and amply demonstrates both musicians’ sensitive style. The second movement brightens things up considerably: a light, playful romp. The composer marks the third movement Adagio molto, very slow, and the two players give it an extra degree of delicacy. It’s quite beautiful, rapturous, actually. By the finale, an Allegro con fuoco, things take a decidedly modern turn, although Monteiro and Santos modulate the conflicts to keep it in line with the honeyed flavor of the earlier movements.

Next up, we get the Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Piano in G major, completed in 1927 by French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Monteiro and Santos consider it important because two of Bela Bartok’s sonatas influenced it and because it was the final chamber work Ravel would write. When it premiered, it featured George Enescu on violin and Ravel himself on piano. It sounds typical of Ravel, full of dreamy impressionism, which Monteiro is especially keen on communicating. Yet the violinist never lets it become swoony or sentimental. The second movement is titled “Blues,” obviously patterned after the American jazz idioms becoming so popular in the day. Monteiro and Santos pull it off with an easy assurance. There seems little beyond their range. The third and final movement is a “Perpetuum mobile,” an allegro that wraps up the proceedings in a kind of whirlwind fashion. Again the players are letter perfect in their handling of the mood and flavor of the piece.

The final selection is the Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Piano Fantasia by Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959). It apparently got a lukewarm reception in its first performances but picked up enthusiastic support a few years later after some revision and its publication in 1933. Like much of Villa-Lobos’s music, it is rich, vibrant, and charmng throughout, and Monteiro and Santos give it its due. Their playing is spirited yet refined, vivacious yet sensitive, and always colorful. This piece wraps up another enchanting album by a pair of gifted musicians.

Producers Bruno Monteiro and Dirk De Greef and engineer Jose Fortes recorded the music at ISEG Concert Hall, Lisbon, Portugal in December 2021. You couldn’t ask for better sound. Both the violin and the piano are about as realistic as being in the room with them. Crisp definition, exceptional clarity, yet smooth and natural, the sound is first-class in every respect.

JJP

To listen to a brief excerpt from this album, click below:

By Karl W. Nehring

Jóhannsson: Drone Mass. One Is True; Two Is Apocryphal; Triptych in Mass; To Fold & Remain Dormant; Diving Objects; The Low Drone of Circulating Blood, Diminishes with Time; Moral Vacuums; Take the Night Air; The Mountain View, The Majesty of the Snow-clad Peaks, From a Place of Contemplation And Reflection. Paul Hiller, conductor; American Contemporary Music Ensemble (Clarice Jensen, artistic director and cello; Ben Russell, violin; Laura Lutzke, violin; Caleb Burhans, viola); Theatre of Voices (Else Torp, Kate Macoboy, Signe Asmussen, Iris Oja, Paul Bentley-Angell, Jakob Skjoldborg, Jakob Bloch Jespersen, Steffen Bruun). Deutsche Grammophon 483 7418.

Here we have another recording of music from the late Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannson (1987-2018), whose compositions have been reviewed several times before in Classical Candor. Jóhannson was a composer with a rich imagination who was fascinated with sounds, so you never quite knew what he might come up with next. As the liner notes characterize it, “Drone Mass is an electroacoustic oratorio. It can also be seen as an exercise in apophenia – the tendency of the human brain to draw connections between apparently unrelated things, to find patterns and meanings where none was intended. As the composer himself admitted, he was inspired by the musical concept of the drone, but he was also keenly aware of the drones that patrol our skies. ‘I have no specific thoughts about how these ideas relate to each other,’ he wrote, ‘but for me they have some kind of poetic resonance, which is usually enough for me.’ Despite its title Drone Mass is neither a setting of the Mass nor a piece that simply drones. In fact, much of it is full of movement.” Jóhannsson based his text on the so-called “Coptic Gospel of the Egyptians,” part of the Nag Hammadi library discovered in 1945, including a hymn described as consisting of “a seemingly meaningless series of vowels.” The work’s premier performance took place in 2015 at the Egyptian Temple of Dendur space in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Augmenting the ACME players were the vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth, with the composer himself controlling the waves of electronic sound. The album reviewed here was recorded during May 2019 at the Garnisonskirken in Copenhagen. It was produced by Francesco Donadello, another friend and regular associate of Jóhannsson’s. ACME were joined by the Danish vocal group Theatre of Voices and their Artistic Director Paul Hillier. They too have a very close connection with Drone Mass, having performed it twice in the US, and in Krákow, with Jóhannsson and ACME. Most recently, ACME and Theatre of Voices gave a further performance in Athens, just four months after the composer’s death. Theatre of Voices also appear on other recordings of Jóhannsson’s work, including Orphée, Englabörn & Variations, Arrival, and Last and First Men.

Although the idea of electronics, a seemingly meaningless series of vowels, and even the very idea of a “drone mass” itself might sound forbidding and off-putting, the music itself is not so. Rather, it is music that is engaging and immersive, drawing the listener in with its interweaving of the mysterious and the familiar, the acoustic and the electronic, the ancient and the contemporary, the ephemeral and the eternal. At the opening, the sounds are those of the voices, captured in the large space of the church in which they were recorded, gradually joined by the string instruments. As the piece unfolds, electronic sounds become more prominent, adding texture and power as they make their dramatic entrance in To Fold & Remain Dormant and add a feeling of otherworldliness to The Low Drone. I would imagine that by now the more conservative among our readers have decided that they will take a pass on this one, the more adventurous are willing to give it a listen, and those in the middle are not quite sure just what to think. To this last group, I strongly encourage you to give Drone Mass an audition, at least if you have an interest in imaginative vocal music. (And hey, give it a try on a good set of headphones, preferably wired.)

Haydn 2032: No. 10 – Les Heures du Jour. Haydn: Symphony No. 6 in D Major “Le Matin”; No. 7 in C Major “Le Midi”; No. 8 “Le Soir”; Mozart: Serenade No. 6 in D Major, K.239 “Serenata Notturna”. Giovanni Antonini, Il Giardino Armonico. Alpha Classics ALPHA 686.

Lest any followers of Classical Candor get the idea that all I ever listen to or recommend is contemporary music such as that recommended above and below, allow me to present some evidence to the contrary. When it comes to honest-to-goodness true-blue through-and-through classical music, I must say in all candor that you really can’t beat good old Papa Haydn, and hey, Mozart’s not too shabby, either. This release is from a series that looks forward to the three hundredth anniversary of Haydn’s birth in 2032, a series with the ambitious goal of recording all 107 of the composer’s symphonies. Although as you can see from the heading that the three symphonies presented here are in numerical order, you can also see that this release is No. 10 in the series (and no, I have not auditioned any of the previous releases, although I plan to look into them). So what gives? How can recording number 10 of 107 symphonies comprise Symphonies Nos.6-8? And how did Mozart sneak in there? The answers can be found in the liner notes: “Seeing the music of Haydn as ’a kaleidoscope of human emotions’, Giovanni Antonini has decided to tackle the symphonies not in chronological order , but in thematically based programmes (‘La passione’, Il filosofo’, ‘Il distratto’, etc.). Moreover, the Italian conductor believes it is important to establish links between these works and pieces written by other composers contemporary with Haydn or is in some way connected with him.” The theme of this release is “the hours of the day,” as we have the three Haydn symphonies representing morning, noon, and evening, followed by the nocturnal serenade penned by Mozart. This is music that is colorful, sprightly, and at once both elegant and charming. The size and the sound of this Italian period-instrument chamber orchestra seem perfectly suited to this music, making for an utterly delightful release.

Thomas Larcher: Symphony No. 2.”Kenotaph.” Die Nacht der Verlorenen. Andre Schuen, baritone; Hannu Linto, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Ondine ODE 1393-2.

Thomas Larcher (b. 1963) is an Austrian composer and pianist. Interestingly enough, his name sounded vaguely familiar to me, so I did a little digging. Aha! I discovered that he had made some recordings on the ECM label as far back as 1999, when he released an album of piano music by Schubert and Schoenberg. Here, of course, he appears in his role as composer, this new Ondine release featuring two of his orchestral compositions. The first is his Symphony No. 2, “Kenotaph” (2015-2016). The liner notes explain that “a cenotaph, from the Greek, is a term used for a monument which is in the shape of a tomb but which is empty, serving as a memorial for deceased persons buried elsewhere. Cenotaphs have traditionally been erected to honour those who have died in combat and remained on the battlefield, but with Larcher’s work the subtitle was motivated by the painful awareness of the thousands of refugees who have drowned in the Mediterranean. The work can also be understood as a more general meditation on human tragedy and an exploration of profound existential issues.” The work is reminiscent in some ways of Mahler, but not in a nostalgic way. Larcher cuts his own path, making his own individual statement while revealing his roots in the Viennese tradition. The two outer movements are the most intense and “modern sounding,” while the two inner movements, marked II. Adagio and III. Scherzo, Molto Allegro, respectively, are comparatively more straightforward sounding but entertainingly imaginative in the style of Mahler, but yet with a more modern sonority. This is music that is utterly fascinating, music that will make you want to listen again and again. Some listeners might be put off by the brashness of the opening measures, but I would urge them to be patient and give the symphony a chance. Let the two inner movements work their magic; once they do, the outer movements may begin to have more meaning. The song cycle Die Nacht der Verlorenen (“The Night of the Lost”) from 2008 takes as its text poems by the Austrian author Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973). The music is generally on the slow side, but expressive and colorful. Schuen’s voice is quite gripping; if you read the text, you will understand why, as the poems are quite dark. As we have come to expect from Ondine, the sound quality is excellent, with plenty of impact. As an added bonus, the liner notes are helpful, offering useful insights into the music. This may not quite be a release for everyone, but if you are a fan of the music of Mahler, then Larcher is someone you really might want to check out.

Elgar-Bridge: Cello Concertos. Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85; Bridge: Oration (Concerto elegiaco). Gabriel Schwabe, cello; Christopher Ward, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra. Naxos 8.574320.

I suspect that there are many classical music lovers who have more than one recording of the Elgar Cello Concerto in their collection. I suppose, then, I should just cut right to the chase and say that the folks at Naxos have released another one they might want to consider adding. First of all, Schwabe does a fine job. His account is swift and virtuosic, but he never seems to take things over the top. Likewise the orchestral accompaniment provided by Ward and his Vienna forces, who provide a nimble, clean, committed sound. All in all, this is a refreshingly straightforward performance. There are times when I might want to hear the heart-on-sleeve emotion of du Pré, but that is not the only way to play the Elgar. Another reason to pick up this release is the coupling, which is an unusual one, Frank Bridge’s Oration (Concerto elegiaco) from 1930. According to the liner notes, “the subtitle Concerto elegiaco was the score’s original title, but, according to Florence Hooton, the composer changed that to Oration in order to emphasize his conception of the work as a funeral address and an outcry against the futility of war, with the solo cello as orator.” Schwabe is able to make his cello play that role perfectly, making it sing out passionately with deeply felt emotion. Oration is a musically moving piece that deserves to be heard; kudos to Naxos for including it here. Off the top of my head I can think of three outstanding Elgar Cello Concerto recordings that are paired with performances of pieces/performances that deserve to be heard: The Jacqueline du Pre/Sir John Barbirolli Elgar paired with Janet Baker’s performance of Elgar’s Sea Pictures; the Inbal Segev/Marin Alsop Elgar paired with Segev’s performance of Anna Clyne’s Dance; and this one. I’m sure there are others, but I can personally attest to these three. Enjoy!

KWN

Music of Wood, Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Elgar. David Bernard, Park Avenue Chamber Symphony and Wind Ensemble. Recursive Classics RC5946217.

By John J. Puccio

“This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for her self

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in a silver sea

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”

--William Shakespeare, Richard II

England had a musical renaissance in the late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century with the so-called “English pastoral school.” Composers of this persuasion strove to create (or some would say revive) a singular style of music making based on recreation of seventeenth-century tunes and collected traditional songs. In general, the music celebrated the joys of the countryside, the life of shepherds or rural folk, usually peaceful, innocent, idyllic, and often programmatic music. The current album offers four composers representing this musical school of thought: Haydn Wood, Gustav Holst. Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sir Edward Elgar.

David Bernard and his Park Avenue Chamber Symphony and Park Avenue Wind Ensemble present the selections. As you probably know by now, my having mentioned it often, the Park Avenue ensemble includes mainly players who do other things for a living (like hedge-fund managers, philanthropists, CEO's, UN officials, and so on). They're not exactly amateurs, but they're not full-time musicians, either. Fortunately, their playing dispels any skepticism about the quality of their work; everyone involved with the orchestra deserves praise. Nor is the Park Avenue Chamber Symphony a particularly small group. It's about the size of a full symphony orchestra but play with the transparency and intimacy of a chamber group.

Opening the program is Mannin Veen--”Dear Isle of Man”--A Manx Tone Poem by Haydn Wood (1882-1959). Basing the work on folk songs from the Isle of Man, Wood wrote it in 1933 for full orchestra and later arranged it (or had it arranged) for wind ensemble. Maestro Bernard offers it here in its arrangement for wind ensemble, which became the most-popular medium for the work. Personally, I had my doubts, thinking a wind ensemble was the last thing a peaceful, bucolic, “pastoral” piece of music needed. But the Park Avenue Wind Ensemble proved me wrong. There is nothing bombastic or overblown about the Suite’s six movements. The playing under Maestro Bernard is mostly gentle, sweet, and comforting, an ideal setting for the music.

Next, we get the Suite No. 1 in E-flat for Military Band by Gustav Holst (1874-1934), who, yes, really did write more than just The Planets. Holst wrote the Suite in 1909, a few years before The Planets, and while the tunes in the Suite might sound like folk songs, they were all original to the composer. It’s probably the least “pastoral” of all the selections on the album, but it shows a fine, spunky drive, with a military cadence and bearing throughout, culminating in a full-fledged march by the end. Again, the wind ensemble carry out their duties with an affectionate glee.

After that, we get the familiar Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958). Written in 1909, it is clearly derived from the composer’s interest in Tudor music, which itself was seeing a revival about this time. Here, we have the symphonic orchestra back, and they do a lovely job under the commanding leadership of Maestro Bernard. There’s nothing wishy-washy about this account. Bernard leads them boldly, with strong, firm, resolute direction. Thus, the music sheds much of the sentimentality from which it sometimes suffers.

The final and longest piece on the disc is Variations on an Original Theme (“Enigma”) by Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934). He wrote it in 1888, but his publisher wasn’t so sure of its success so appended the subtitle “Enigma” to it in the hope that it would generate more interest. (Several years earlier, Tchaikovsky had declared that his own “Pathetique” Symphony had an underlining meaning, which had caused a good deal of intrigue over what that obscure meaning might be. Elgar’s publisher hoped the same buzz might come of an “Enigma” subtext.)

Whatever, the Elgar piece contains the theme itself and fourteen variations, the most famous probably being the ninth variation Adagio, “Nimrod.” The variations began life as improvisations that Elgar continued to toy with, bringing in all sorts of clever, hidden, and not-so-hidden meanings (thus, “Enigma”). Elgar dedicated the music “to my friends pictured within,” with each variation being a musical sketch of one of his close acquaintances. Anything else that listeners might want to bring to the music is up the them. The important thing is that Maestro Bernard and his orchestra play the music in a most forthright manner, making it more heartfelt in the process. The interpretations dance lightly when necessary, display a cheerful playfulness at other times, and exhibit the proper decorum where appropriate. It’s an altogether delightful and clearheaded rendering of the score.

Recording engineers Jennifer Nulsen, Isaiah Abolin, Thom Beemer, Gunnar Gillberg, and Lawrence Manchester recorded the music at the DiMenna Center for the Performing Arts, NYC in February and November 2021. The recording shows a healthy degree of hall resonance, making for a little less overall transparency but a good deal of realistic ambience. The sound is well balanced in most respects, with a soft, warm glow making it easy to listen to.

JJP

To listen to a brief excerpt from this album, click below:

By Karl W. Nehring

Schubert: Piano Sonata in G major D894; Piano Sonata in E minor D769a (fragment; formerly D994); Piano Sonata in A major D664. Stephen Hough, piano. Hyperion CDA 68370.

The last time British pianist Stephen Hough (b.1961, his name rhymes with “rough”) made an appearance in Classical Candor, it was for reviews of both a recording (Chopin’s complete Nocturnes) and a book (Rough Ideas), which can be found here: https://classicalcandor.blogspot.com/2021/11/piano-potpourri-no-2-cd-reviews.html. Given that the piano music of Schubert is second to none, at least in my humble estimation, I had been looking forward eagerly looking forward to auditioning this new recording and was grateful for its arrival. Not long ago I had it playing on my big system and was sitting in my listening room with my eyes closed, not so much listening critically but just letting myself get lost in the music, when I was startled by a sharp tap on my shoulder. As I turned to see what my wife wanted, I was startled to see that it was not my wife, but rather my Belgian detective friend, whom I had forgotten had said would be in the area in April and would try to stop by for a quick visit. As I scrambled for the remote to turn down the volume, he quickly exclaimed, “No no, mon ami, I am quite enjoying the Schubert most exquisite!” Hearing that, I immediately invited him to take my place in the listening chair. Removing a handkerchief from his pocket, he carefully dusted off the chair before primly sitting himself down. As he settled in to listen more closely, there was at first a look of intense concentration on his face, then a hint of a smile on his lips and a twinkle in his eyes. At times, his fingers would twitch as though he were fighting the urge to play the music on some imaginary keyboard. As the music came to an end, he turned to me and said, “Ah, mon ami, that was playing of the kind most exquisite. This fellow, he does to the music of Schubert the great justice, n’cest-pas?” Once again, far be it from me to argue with the world’s greatest detective.

As he did in the Chopin, Hough brings an interpretive touch to the music of Schubert that somehow sounds “just right.” He puts plenty of emotion and feeling into his playing, but never takes it over the top. You can feel his great love for this music, but his interpretations never sound overly sentimental. Moreover, the warmth of his playing is enhanced by the warmth of the recording. The Hyperion label has got piano recording down to an art and a science. They know how to put just enough distance between the microphones and the piano (and just where to put those microphones, how many, what types, etc.) and how to mix and master the resulting feeds to make the recording sound natural in your listening room. Perhaps some listeners might prefer a closer, brighter sound, but for me, this is about as good as it gets. The music of Schubert, the artistry of Hough, and the production values of Hyperion (not just the engineering, but also first-class liner notes and cover art) make this a highly recommendable release.

Arc I. Granados: Goyescas; Janacek; In the Mists; Scriabin: Piano Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass.” Orion Weiss, piano. First Hand Records FHR127.

Ohio-born pianist Orion Weiss (b. 1981) is embarking on a recording project that will eventually yield three releases, Arc I being the first. In his liner note essay, Weiss explains that “the arc of this recital trilogy is inverted, like a rainbow’s reflection in water. Arc I’s first steps head downhill, beginning from hope and proceeding to despair. The bottom of the journey, Arc II, is Earth’s center, grief, loss, the lowest we can reach. The return trip, Arc III, is one of excitement and renewal, filled with the joy of rebirth and anticipation of a better future.” He goes on to give a quick preview and chronological overview: Arc I (Granados, Janacek, Scriabin) from before World War I; Arc II (Ravel, Shostakovich, Brahms) from during World Wars I and II, during times of grief; Arc III (Schubert, Debussy, Brahms, Dohnanyi, Talma) from young composers, times of joy, after World War I and after World War II.

As Arc I begins, both the quality of the engineering and the quality of the musicianship reveal themselves quickly. In the Goyescas, Weiss displays a delicate touch that gives a dreamy feel to the music as it begins to unfold. His fingers are able to manipulate the keyboard with a delicacy and grace that can’t help but draw the listener in. The Janacek composition In the Mists evokes a different mood – unsettled, uncertain, soft one moment and loud the next. Weiss says of this piece that “its ideas grow organically and unpredictably, as if in conversation or thought, and the borders between accompaniment and melodic material disappear… the work ends with despair and without resolution, stuck in hopeless, fragmented repetition.” Weiss shows that he can play with power when called for, but he still displays that soft touch when called for. Shifting then to the music of Scriabin, the mood really does shift once again, the music of Scriabin being more complex, more bold and assertive, although at times becoming quiet and mysterious. Weiss proves capable of deftly navigating these twists and turns, drawing the listener into a mysterious soundscape. If Arcs II and III maintain this level of excellence, Weiss will have produced something truly special indeed. For now, Arc I is well worth a listen.

Brian Wilson: At My Piano. God only Knows; In My Room; Don’t Worry Baby; California Girls; The Warmth of the Sun; Wouldn’t it be Nice; You Still Believe in Me; I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times; Sketches of Smile: Our Prayer/Heroes and Villains/Wonderful/Surfs Up; Surf’s Up; Friends; Till I Die; Love and Mercy; Mt. Vernon Farewell; Good Vibrations. Brian Wilson, Piano. Decca B0034672-02.

Most people of a certain age probably recognize Brian Wilson (b. 1942) as the creative force behind the rock group The Beach Boys, who first made waves singing about surfing and hot rods but then made their biggest splash with the recording that Brian masterminded, nearly driving the rest of the group and assorted studio musicians crazy with his demands but ending up with an album that is widely acknowledged as a popular music milestone, Pet Sounds. Sir Paul McCartney, for example, freely acknowledges that it was hearing what Wilson and his bandmates had achieved with Pet Sounds that spurred the Beatles to put forth the many hours of extra effort in the studio that it took to produce their own legendary response to Wilson’s masterpiece, 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Pushing for ever more complex harmonies and sounds, Wilson went on to experience some well-publicized mental health issues, dropping out of the music scene for an extended period before making a comeback, recording some solo work, briefly reuniting with the remaining Beach Boys (who have since split – Mike Love still fronting the group along with some of the original members, Wilson occasionally touring with other members as “Brian Wilson and Friends,” playing many of the old tunes, sometimes recreating entire albums).

When I first heard that his newest release was to be titled “At My Piano” and was going to consist of old material from Wilson’s catalog, I assumed that he would be singing, at least on some of the cuts. Although at this point in his life he does not have much of a voice, there is a raw, sincere honesty to it that can just break your heart on songs such as “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times'' or “Love and Mercy.” At first, then, I was dismayed to learn that this was to be a purely instrumental album, just Brian at the piano, playing his own arrangements of music that he obviously knows inside out and backwards. On first listen, I enjoyed it, but was not quite sure what I thought of it. So I listened again. Lather, rise, repeat… I read what he wrote in his brief liner note. “We had an upright piano in our living room and from the time I was 12 years old I played it each and every day. I never had a lesson, I was completely self-taught. I can’t express how much the piano has played such an important part in my life. It has brought me comfort, joy, and security. It has fueled my creativity as well as my competitive nature. I play it when I’m happy or feeling sad. I love playing for people and I love playing alone when no one is listening. Honestly, the piano and the music I create on it has probably saved my life.” If you are familiar with the music of the Beach Boys, you will be familiar with this music, and might even find yourself mentally, or perhaps – if nobody is listening – singing right out loud some of the lyrics out loud to Brian’s accompaniment. That’s okay, it’s hard not to. Alternatively, you can just play this CD or stream this release and enjoy listening to what Brian does with this music without necessarily singing along. That’s okay too. No, this is not Schubert, or Beethoven, or Chopin; admittedly, many classical music fans may think I am wasting their time by even including this review. I am sorry to have wasted their time, but I hope that there are at least a few folks who find this review a pleasant surprise. And to all, I suggest taking a look at the smile on Brian Wilson’s face and taking a moment to contemplate the joy he felt in performing his music for you.” Love and mercy to you and your friends tonight…”

Oscar Peterson: A Time for Love (The Oscar Peterson Quartet Live in Helsinki, 1987). CD1: Sushi; Love Ballade; A Salute to Bach (Medley): Allegro/Andante/Bach’s Blues; Cakewalk; CD2: A Time for Love; How High the Moon; Soft Winds; Waltz for Debby; When You Wish Upon a Star; Duke Ellington Medley: Take The “A” Train / Don’t Get Around Much Anymore / Come Sunday / C-Jam Blues / Lush Life / Caravan; Blues Etude. Oscar Peterson Quartet (Oscar Peterson, piano; Joe Pass, guitar; Dave Young, bass; Martin Drew, drums). Mack Avenue MAC1151.

The late Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson (1925-2007) was regarded as one of the true giants of the keyboard. He released more than 200 recordings, accrued seven Grammy awards, and was held in high regard amongst his peers. He released a number of recordings of the Oscar Peterson Trio, which consisted over the years of Peterson on piano plus some combination of bassist, drummer, or guitarist. Of course, he also recorded many solo and duo performances. Occasionally, Peterson sat in as a sideman on other musicians’ recording sessions, with some critics contending that he did some of his best playing in that context rather than a leader. Here we have him heading a quartet that includes another noted virtuoso of his instrument, guitarist Joe Pass. With two well-filled discs, Peterson fans will find plenty to keep them entertained. CD1 includes five compositions by Peterson himself, the longest (20:39) being the enticingly titled (at least for classical music fans) “A Salute to Bach.” Although to these ears at least it does not sound all that much like Bach (although the middle section, Andante, gets into some Bach-like counterpoint), it swings, and fits in with the rest of the tunes, which are generally lively and designed to get your toe tapping. The second CD consists primarily of music by others; to be honest, I think this is the disc that most listeners will prefer. Highlights include Pass’s solo guitar work on “When You Wish Upon a Star'' followed by the whole quartet really digging into a half-dozen Ellington/Strayhorn tunes. Fun stuff! And for a 35-year-old live recording, the sound quality is remarkably good. If you are a fan of the mainstream sort of jazz that Oscar Peterson represents, A Time for Love is a recording well worth seeking out.

KWN

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations. Alia Vox AVSA9946 (3-disc set).

By John J. Puccio

The Spanish conductor, composer, and violist Jordi Savall (b. 1941) has been a leader in the fields of historically informed performances and period-instrument bands for a very long time, having formed Hesperion XX (now XXI) in 1974, La Capella Reial de Catalunya in 1987, and Le Concert des Nations in 1989. In his career he’s made over a hundred recordings (mostly for EMI, Astree, and more recently for his own label, Alia Vox) and appeared in just about every concert house everywhere in the world. While usually sticking with Baroque and early classical music, he has also branched out with music of the early Romantic Age, like these Beethoven symphonies. Here, with Symphonies Nos. 6-9, he follows his earlier set of Nos. 1-5 (2020).

Unlike some HIP conductors who take such an intensely academic approach to their music making that it tends to drain the life out of it or yet other conductors who seem committed to whipping through it so fast we don’t get time to appreciate it, Savall has always taken a different path. His style, though always well researched and enlightened, has also been unfailingly joyful and robust. Although his performances have not always sounded the most refined, they have always been delightful and heartfelt. And so it is with his Beethoven.

Of course, Savall isn’t the first one to record all of the Beethoven symphonies using period instruments, historically informed performance practices, accurately sized ensembles, technically correct bowing, and the composer’s own tempo markings. You’ll remember, Roger Norrington and his London Classical Players were among the first to attempt this feat back in the 1980’s. But not all HIP conductors succeed in making the music more enjoyable than those employing traditional interpretations using modern orchestras. Take, for instance, the matter of tempos. When Beethoven got older he embraced the newly patented metronome with a passion, perhaps to ensure that later generations would play his music the way he intended. Whatever, later generations were divided over the composer’s rather fast metronome markings, many critics suggesting that the metronome Beethoven used must have been faulty. Needless to say, as the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries wore on, conductors came to adopt their own tempos and pretty much ignored Beethoven’s. These days, thankfully, we have greater choice in such matters. Savall, for example, follows Beethoven’s markings pretty carefully and is within seconds of Norrington’s speeds in most movements. Yet Savall’s accounts couldn’t be more different from Norrington’s.

As the first disc in Savall’s set contains the Sixth Symphony “Pastorale,” it makes a good comparison. I have always felt it was the weakest of Norrington’s recordings because he followed Beethoven’s tempos so rigidly that it rather took away some of the gentle warmth of the music. Not so with Savall, whose quick tempos never sound fast and breathe new life into the score. Instead of sounding somewhat cold and sterile, as Norrington sounds to me in the Sixth, Savall’s version is far friendlier, more radiant, more alive. Indeed, I would count this recording among the best accounts of the “Pastorale” from anybody, HIP or traditional, and that includes my favorites from Bohm, Walter, Reiner, Jochum, Klemperer, and the rest. Savall's way with the “Arrival in the country” is full of good cheer; the “Scene at the brook” is tranquil and serene; the “Merry gathering of peasants” is sensibly spirited without appearing boisterous or rushed; the “Storm” is appropriately menacing: and the concluding “Shepherd's song” and “Happy feelings after the storm” are gentle, bucolic, and carefree, taken more effortlessly than most other period-instrument bands. Beethoven wanted us to picture the scenes of the “Pastorale” in our mind, and that’s exactly what Savall helps us do. Altogether, he makes a fine show of it, producing as good an interpretation as anyone’s and better than most.

Disc two gives us the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies. The Seventh, as you know, is the one that Beethoven himself said was one of his best pieces of work, the one whose second movement Allegretto became so popular that audiences would often demand it as an encore, and the one that Richard Wagner called the “apotheosis of the dance,” thanks to its bouncy, dance-like rhythms. It is a work that seems tailor-made for Maestro Savall, who generates thoroughly zesty results without sounding frenetic. His performance is much like the one I reviewed a short while back from von der Goltz and the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, both of them conveying exuberance, spontaneity, and affection in equal measure.

Beethoven called No. 8 “my little Symphony in F,” and so audiences have referred to it for years. Compared to the more massive symphonies that precede and follow it, it really is somewhat small, being only about twenty-five to thirty minutes in length (although Savall gets through it in just under twenty-five minutes). It’s also one of the composer’s more seriously lighthearted works (with the exception of the final movement, at least), and the composer could never understand why it didn’t receive the same accolades as his longer symphonies did. I think it does get rather swallowed up by its surroundings. In any case, Savall provides the music with a healthy playfulness and vivacity, helping us to see it as a natural extension of and worthy successor to No 7.

The third and final disc in the set contains Beethoven’s crowning jewel, the Ninth Symphony. For me, this makes Savall’s account of the piece a tad disappointing because it’s the one symphony in the collection where the slightly faster-than-traditional speeds aren’t quite able to convey the full grandeur and opulence of the music. Remember when compact discs were first introduced, Sony and Philips, the co-developers of the CD, told us they designed it to hold about seventy-five minutes because they wanted the entire Ninth Symphony to fit on one disc. Well, Savall brings it in at just under sixty-three minutes, so there’s plenty of space to spare. Still, the recording makes a fascinating and worthwhile listening experience, and, overall, it’s better than most of the other historically informed, period-instrument interpretations of the work I’ve heard.

Savall opens the Ninth with a brawny vigor, where the timpani tend to dominate. The second movement, marked Molto vivace, is certainly that, very brisk and snappy. This seemed to me the most successful of the movements in its abundance of sparkle within a framework of elegant nobility. The third movement Adagio seemed a trifle brusque to me, too businesslike to be as moving as I’ve heard it. The final-movement Presto opens what has become one of the most-famous stretches of music in the whole of the classical world. Under Savall it appeared to me a trifle perfunctory; nevertheless, it provides a suitable introduction to the big choral number that follows. The soloists and chorus also serve the music well, although they are not as impressive as I’ve heard in some more-conventional performances.

The packaging is a fold-out Digipak sort of affair that’s about as easy to operate as an old road map. The booklet insert is over 270 pages long and written in practically every language known to Man. I found this document quite comprehensive and a welcome addition to the set. Just don’t try taking it out of the case; it’s a devil to put back in.

Producer and engineer Manuel Mohino recorded the symphonies at La Collegiale du Chateau de Cardona, Catalonia, Spain and the National Forum of Music, Wroclaw, Poland in 2020-21. Alia Vox chose to make it in hybrid SACD multichannel and stereo, depending on the equipment you use for playback. I listened in SACD two-channel stereo.

The sound (especially for Nos. 6, 7 and 9, recorded in Spain) is spacious, wide-ranging, smooth, dynamic, well balanced, and well defined. It is, in fact, about as good as one could want. The only minor caveat I found was that the soloists are recorded fairly closely. Nonetheless, the chorus doesn't shrill out on us. Compared to all the other period-instrument performances I’ve auditioned, the sound here is clearly the best, the most-realistic, so you really won’t do any better. No. 8, recorded separately from the others, is a tad more resonant and slightly less transparent than the others but still quite good.

JJP

To listen to a brief excerpt from this album, click below:

By Karl W. Nehring

Florence Price: Symphony No. 3 in C minor; The Mississippi River; Ethiopia’s Shadow in America. John Jeter, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Radio Symphony Orchestra. Naxos 8.559879.

Florence Price: Symphonies Nos. 1 & 3. Yannick Nézet-Séguin, The Philadelphia Orchestra. Deutsche Grammophon B0034879-02.

The American composer Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. As a child in the South, she was rejected by white teachers, so she received her first musical training from her mother. As the liner notes of the DG release explain, “because advanced training was largely unavailable to women of color in the South, 16-year-old Price was enrolled in the New England Conservatory in Boston, majoring in organ and piano performance (while following her mother’s advice to present herself as being of Mexican descent). [As an aside, watching the performance of some of our white GOP Senators during the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson as I write these words leaves me more than a little angry and skeptical about racial

and political matters in 2022 America, I’m sorry to have to say but I just can’t in good conscience let it go unsaid…] At the NEC she was taught music theory by the institution’s director George Whitfield Chadwick, a leading figure of the so-called Second New England School of composers who had a special interest in African-American folk melodies and rhythms. He used a pentatonic melody resembling a spiritual in a symphony seven years before Dvorak’s “New World'' Symphony of 1893.”

Although what we have here are two recordings on different labels featuring performances of the same major work, Symphony No. 3 by, my intention is not at all to present this as any sort of competitive review. If anything, these CDs complement and even supplement each other. Other than the Symphony No. 3, of course, the two releases are completely different, the DG giving us Price’s Symphony No. 1 while the Naxos includes two of her orchestral suites. All of these works are well worth an audition, another way in which the releases complement more that they compete.

Let me first briefly discuss the music not in common between the two releases. In Symphony No. 1, you can hear echoes of Dvorak (and the influence of Chadwick, or at least I think that would be a reasonable guess), not that there’s anything wrong with that. In the third movement, however, rather than a traditional scherzo, Price treats us to a movement based on an African dance known as “Juba,” which involves syncopated rhythms and body slapping. Of course we do not get the latter from the orchestra, but there are some lively rhythms from the percussion section as the music moves along in lively fashion. Again, those who love the music of Dvorak (think, for example, of his Symphony No. 8, with its stretches of dance rhythms) will find much to love in this symphony. The two tone poems on the Naxos CD on the Naxos CD are also quite enjoyable. Although in The Mississippi River, Price works in quotations from several well-known spirituals and folk tunes, this is not a lighthearted romp; rather, it is a serious, thoughtful composition that bears repeated listening. Likewise, Ethiopia’s Shadow in America, one of the few compositions for which Price provided a written narrative, is colorfully scored and certainly enjoyable.

Symphony No. 3 (her Symphony No. 2, sadly enough, has been lost forever) sounds less overtly like Dvorak but still has that familiar idiomatic vibe. As the Naxos liner booklet explains, “a letter written before the symphony’s premiere offers one of the only first-hand accounts of Price’s compositional approach. ‘It is intended to be Negroid in character and expression,’ she wrote, but ‘no attempt has been made to project Negro music solely in the traditional manner.’ That is, she wanted to project aspects of her cultural heritage in a symphonic framework without making direct references to an existing body of folk songs and dances – a broad creative challenge broached by many composers around the world.” Like the 1st, it too has a Juba-themed third movement rather than a traditional scherzo. The end result is a remarkable symphony that is well deserving of not just one, but two excellent new recordings.

However, although both recordings are excellent, they vary significantly both musically and sonically. Nézet-Séguin takes a broader view of the first two movement than does Jeter, which is evident subjectively as you simply listen, with Nézet-Séguin seeming to draw things out and linger at times while Jeter moves things right along (although he never sounds actually hurried), and objectively as you note the timings: Nézet-Séguin 11:37 and 9:32 for the first two movements versus Jeter at 9:26 and 7:54. That is quite a difference in interpretation; to be honest, I am not sure which I prefer. I’ll just say that they are both enjoyable, and I will add that in the final two movements, the two conductors are within a few seconds of each other. Sonically, the DG release is clean, clear, and full-range, and the world-class Philadelphia Orchestra sounds large and in charge. However, you do not get a firm sense of the space in which the orchestra was recorded (Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia), which becomes evident when you listen to the Naxos release. The ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra was recorded in Studio 6 at the ORF Funkhaus in Vienna, and the recording gives you a sense of the space they were in, which at least for me, establishes a stronger bond with the orchestra. Although the RSO does not sound quite as large or opulent as the Philadelphia ensemble, they play this music with expressive power under the baton of Maestro Jeter, who has been an enthusiastic advocate for the music of Florence Price (he previously recorded her Symphonies Nos 1 and 4 with the Fort Smith Symphony for Naxos) .

Although it might sound like a reviewer copout, I really cannot pick one of these discs over the other. They really are complementary. Were some crazed wacko with an assault rifle to break into my home and force me to choose one or the other, I would probably pick the DG, because I would rather have the two symphonies; however, after he left with my Naxos disc in his backpack I would get on my computer and order a replacement copy of the Naxos, as both releases are musical delights that I simply could not live without, and as you might have guessed by now, I recommend them both with heartfelt enthusiasm. Just as we go to press, the DG recording has been awarded a Grammy for best classical recording of the year.

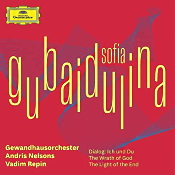

Gubaidulina: Dialog: Ich und Du; The Wrath of God; The Light of the End. Vadim Rapin, violin; Andris Nelsons, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. Deutsche Grammophon 486 1457.

Ir is certainly quite a shift in both style and mood to go from the music of Florence Price to the music of Russian-born composer Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931), who has lived near Hamburg, Germany, for the past 30 years. While the music of Price is flowing and tuneful, the music of Gubaidulina is dense, dark, and at times almost explosive in its impact. However, there is another fascinating dimension to her music, as the liner notes explain: “Sofia Gubaidulina’s miuic exerts its fascination not least as the result of its profound spirituality. ‘Whenever I’m composing,’ the deeply religious nonagenerian admits, ‘I pray, no, I actually speak to God.’ Her works focus on our relationship with God and are private dialogues with the divine. This is also true of the three works that are all appearing here in world-premiere recordings.”

Some will no doubt recognize that Dialog: Ich und Du (Dialogue: I and You), which is the title of her Violin Concerto No. 3, is a reference to the philosopher Martin Buber’s book Ich und Du, which in its English translation, I and Thou, was quite influential in intellectual circles in the 1970s and beyond. The work was written for violinist Vadim Repin, who gave the world premiere in 2018. The performance on this recording is from the work’s German premiere in 2019. You can envision the work as a dialog between Repin’s violin, representing a human, and the full orchestra, representing the divine. There is dialogue, at times pleading, at times tender, until finally, at the end, the violin plays in hushed tones. (Submission? Gratitude? Ecstasy? Exhaustion?)

Next up is the powerful Wrath of God, which opens with a mighty blast from the brass section and builds up simple musical motifs to present an impressively powerful display of what a large orchestra can do when they are given the green light. Beyond its musical virtues, which are considerable, this is a great piece for showing off a good audio system.

The program closes with The Light of the End, which to these ears at least is vaguely reminiscent at times of the music of Sibelius, with its whirling and swirling strings and brooding brass, punctuated by tinkling percussion. It is an energetic work, crackling with energy. According to the notes. “It is based on a fundamental conflict that characterizes the physics of music, namely, the irreconcilability between the natural overtone row and tempered tuning… In Sofia Gubaidulina’s own words, the work encapsulates the ‘irreconcilability of nature and real life, in which nature is often neutralized. Sooner or later, this pain had to be manifested in some composition.’ The work’s title refers to the final section in which the dazzling sonorities of the cymbals afford a ray of hope.” Fear not: although that liner note description might make it sound crazed and unlistenable, the piece is not painful to hear. Energetic, yes, and at times filled with tension, but never to the point of unlistenability. There truly is light at the end – and along the journey.

In the end, these are three remarkable compositions both musically and sonically. They have been well played by the remarkable Gewandhaus musicians under the direction of Maestro Nelsons, with a passionate contribution from violin soloist Rapin, and well recorded by the engineers. If you have an interest in present-day orchestral music, this is a must-hear release. Outstanding!

KWN

Music of Johann Strauss II, Josef Strauss, Eduard Strauss, and others. Daniel Barenboim, Vienna Philharmonic. Sony 19439962512 (2-disc set).

By John J. Puccio

You doubtless know that Vienna’s New Year’s Concerts have been going on since 1941 when the Vienna Philharmonic began its annual custom of offering them, and things haven’t changed much since then. EMI, RCA, DG, Decca, and now Sony are among the many companies that have recorded the VPO’s concerts over the stereo years, and in keeping with the orchestra’s tradition of having no permanent music director, they invite a different conductor to perform the New Year’s duties each year. The New Year’s conductors in recent times have included some of the biggest names in the business, including Herbert von Karajan, Carlos Kleiber, Willi Boskovsky, Claudio Abbado, Lorin Maazel, Seiji Ozawa, Georges Pretre, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Mariss Jansons, Franz Welser-Most, Zubin Mehta, Gustavo Dudamel, Riccardo Muti, Christian Thielemann, Andris Nelsons, and in 2022 the orchestra invited Daniel Barenboim to return.

Maestro Barenboim (b. 1942) is both a noted pianist and a conductor. He has been the leader of such prestigious ensembles as the Chicago Symphony, the Orchestre de Paris, La Scala, and the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, and he is currently the music director of the Berlin State Opera and the Staatskapelle Berlin. He has been making music for quite a long time, and the recordings I’ve always admired most from him are the late Mozart symphonies and piano concertos with the English Chamber Orchestra on EMI. They have hardly been equalled, so we know what to expect from him.

Here’s the current set’s line-up of selections for 2022:

Disc One:

Josef Strauss: Phonix March

Johann Strauss II: Wings of the Phonix Waltz

Josef Strauss: Die Sinene Polka

Joseph Hellmesberger II: Little Advertiser Galop

Johann Strauss II: Morning Papers Waltz

Eduard Strauss: News in Brief Polka

Johann Strauss II: Overture to Die Fledermaus

Johann Strauss II: Champagne Polka

Carl Michael Ziehrer: Night Owls Waltz

Disc Two:

Johann Strauss II: Persian March

Johann Strauss II: A Thousand and One Nights Waltz

Eduard Strauss: Greeting to Prague Polka

Joseph Hellmesberger: Elves

Josef Strauss: Nymphs Polka

Josef Strauss: Harmony of the Spheres Waltz

Johann Strauss II: At the Hunt Polka

Johann Strauss II: The Beautiful Blue Danube Waltz

Johann Strauss II: Radetzky-March

The last time I heard Barenboim conduct a New Year’s Concert was in 2014, and his conducting seemed to me back then lively, sensible, a little sentimental, and perfectly enjoyable. This time, maybe not quite as much. I sensed a small lack of spark to the music, a minor want of sparkle and excitement. Yet, as I say, minor deficiencies, with most of the program going well. Perhaps we should call it maturity. Most conductors as they age tend to slow down, if only a tad, and we often count these latter performances as “mature.” So be it.

Still, there is much lyrical grace to the Strauss waltzes. The familiar Morning Papers waltz, for instance, demonstrates a lovely cadence, an almost stately refinement often missing from the piece. Other, less familiar material, like the Wings of the Phonix are given a gravitas that elevates them to more important status. The galops and polkas that Barenboim intersperses with the waltzes add a note of exhilarating contrast to the proceedings, and most of the time we hear no noticeable slowdown of the conductor’s enthusiasm for the subject matter. Then, too, he handles Die Fledermaus overture with delicacy as well as passion.

The second disc opens with the Persian March, which carries an unexpected dignity with it in addition to the usual martial airs. And so it goes. The Harmony of the Spheres comes off well, too, with a sweetly paced, uncommonly relaxed lilt. Naturally, we couldn’t have a New Year’s Concert without the traditional closing: The Blue Danube waltz and the Radetzky-March. Barenboim’s Danube, it seemed to me, flowed a little lugubriously but maybe we can chalk it up to global warming. And the audience continues to have a good time clapping in time to Radetzky. So all continues right with the world, despite everything we do to upset it.

Producer Friedemann Engelbrecht and engineer Rene Moller and Wolfgang Schiefermair recorded the music live for Teldec Studio Berlin at the Goldener Saal des Wiener Musikvereins, Vienna, Austria on January 1, 2022. This time, it doesn’t sound as though the engineers recorded the orchestra quite as closely as usual. There is a little distance involved, and a good deal of hall ambience, resonance, reverberation. This, of course, enhances the experience of being at the concert live. After all, most people will want the album as a memento of the live event, audience noise and all, not as an audiophile demo record. In this regard, the sound is fine and serves its purpose. It’s certainly dynamic enough.

JJP

To listen to a brief excerpt from this album, click below:

John J. Puccio, Founder and Contributor

Understand, I'm just an everyday guy reacting to something I love. And I've been doing it for a very long time, my appreciation for classical music starting with the musical excerpts on the Big Jon and Sparkie radio show in the early Fifties and the purchase of my first recording, The 101 Strings Play the Classics, around 1956. In the late Sixties I began teaching high school English and Film Studies as well as becoming interested in hi-fi, my audio ambitions graduating me from a pair of AR-3 speakers to the Fulton J's recommended by The Stereophile's J. Gordon Holt. In the early Seventies, I began writing for a number of audio magazines, including Audio Excellence, Audio Forum, The Boston Audio Society Speaker, The American Record Guide, and from 1976 until 2008, The $ensible Sound, for which I served as Classical Music Editor.

Today, I'm retired from teaching and use a pair of bi-amped VMPS RM40s loudspeakers for my listening. In addition to writing for the Classical Candor blog, I served as the Movie Review Editor for the Web site Movie Metropolis (formerly DVDTown) from 1997-2013. Music and movies. Life couldn't be better.

Karl Nehring, Editor and Contributor

For nearly 30 years I was the editor of The $ensible Sound magazine and a regular contributor to both its equipment and recordings review pages. I would not presume to present myself as some sort of expert on music, but I have a deep love for and appreciation of many types of music, "classical" especially, and have listened to thousands of recordings over the years, many of which still line the walls of my listening room (and occasionally spill onto the furniture and floor, much to the chagrin of my long-suffering wife). I have always taken the approach as a reviewer that what I am trying to do is simply to point out to readers that I have come across a recording that I have found of interest, a recording that I think they might appreciate my having pointed out to them. I suppose that sounds a bit simple-minded, but I know I appreciate reading reviews by others that do the same for me — point out recordings that they think I might enjoy.

For readers who might be wondering about what kind of system I am using to do my listening, I should probably point out that I do a LOT of music listening and employ a variety of means to do so in a variety of environments, as I would imagine many music lovers also do. Starting at the more grandiose end of the scale, the system in which I do my most serious listening comprises Marantz CD 6007 and Onkyo CD 7030 CD players, NAD C 658 streaming preamp/DAC, Legacy Audio PowerBloc2 amplifier, and a pair of Legacy Audio Focus SE loudspeakers. I occasionally do some listening through pair of Sennheiser 560S headphones. I miss the excellent ELS Studio sound system in our 2016 Acura RDX (now my wife's daily driver) on which I had ripped more than a hundred favorite CDs to the hard drive, so now when driving my 2024 Honda CRV Sport L Hybrid, I stream music from my phone through its adequate but hardly outstanding factory system. For more casual listening at home when I am not in my listening room, I often stream music through a Roku Streambar Pro system (soundbar plus four surround speakers and a 10" sealed subwoofer) that has surprisingly nice sound for such a diminutive physical presence and reasonable price. Finally, at the least grandiose end of the scale, I have an Ultimate Ears Wonderboom II Bluetooth speaker and a pair of Google Pro Earbuds for those occasions where I am somewhere by myself without a sound system but in desperate need of a musical fix. I just can’t imagine life without music and I am humbly grateful for the technologies that enable us to enjoy it in so many wonderful ways.

William (Bill) Heck, Webmaster and Contributor

Among my early childhood memories are those of listening to my mother playing records (some even 78 rpm ones!) of both classical music and jazz tunes. I suppose that her love of music was transmitted genetically, and my interest was sustained by years of playing in rock bands – until I realized that this was no way to make a living. The interest in classical music was rekindled in grad school when the university FM station serving as background music for studying happened to play the Brahms First Symphony. As the work came to an end, it struck me forcibly that this was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard, and from that point on, I never looked back. This revelation was to the detriment of my studies, as I subsequently spent way too much time simply listening, but music has remained a significant part of my life. These days, although I still can tell a trumpet from a bassoon and a quarter note from a treble clef, I have to admit that I remain a nonexpert. But I do love music in general and classical music in particular, and I enjoy sharing both information and opinions about it.

The audiophile bug bit about the same time that I returned to classical music. I’ve gone through plenty of equipment, brands from Audio Research to Yamaha, and the best of it has opened new audio insights. Along the way, I reviewed components, and occasionally recordings, for The $ensible Sound magazine. Most recently I’ve moved to my “ultimate system” consisting of a BlueSound Node streamer, an ancient Toshiba multi-format disk player serving as a CD transport, Legacy Wavelet II DAC/preamp/crossover, dual Legacy PowerBloc2 amps, and Legacy Signature SE speakers (biamped), all connected with decently made, no-frills cables. With the arrival of CD and higher resolution streaming, that is now the source for most of my listening.

Ryan Ross, Contributor

I started listening to and studying classical music in earnest nearly three decades ago. This interest grew naturally out of my training as a pianist. I am now a musicologist by profession, specializing in British and other symphonic music of the 19th and 20th centuries. My scholarly work has been published in major music journals, as well as in other outlets. Current research focuses include twentieth-century symphonic historiography, and the music of Jean Sibelius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Malcolm Arnold.

I am honored to contribute writings to Classical Candor. In an age where the classical recording industry is being subjected to such profound pressures and changes, it is more important than ever for those of us steeped in this cultural tradition to continue to foster its love and exposure. I hope that my readers can find value, no matter how modest, in what I offer here.

Bryan Geyer, Technical Analyst

I initially embraced classical music in 1954 when I mistuned my car radio and heard the Heifetz recording of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto. That inspired me to board the new "hi-fi" DIY bandwagon. In 1957 I joined one of the pioneer semiconductor makers and spent the next 32 years marketing transistors and microcircuits to military contractors. Home audio DIY projects remained a personal passion until 1989 when we created our own new photography equipment company. I later (2012) revived my interest in two channel audio when we "downsized" our life and determined that mini-monitors + paired subwoofers were a great way to mate fine music with the space constraints of condo living.

Visitors that view my technical papers on this site may wonder why they appear here, rather than on a site that features audio equipment reviews. My reason is that I tried the latter, and prefer to publish for people who actually want to listen to music; not to equipment. My focus is in describing what's technically beneficial to assure that the sound of the system will accurately replicate the source input signal (i. e. exhibit high accuracy) without inordinate cost and complexity. Conversely, most of the audiophiles of today strive to achieve sound that's euphonic, i.e. be personally satisfying. In essence, audiophiles seek sound that's consistent with their desire; the music is simply a test signal.

Mission Statement

It is the goal of Classical Candor to promote the enjoyment of classical music. Other forms of music come and go--minuets, waltzes, ragtime, blues, jazz, bebop, country-western, rock-'n'-roll, heavy metal, rap, and the rest--but classical music has been around for hundreds of years and will continue to be around for hundreds more. It's no accident that every major city in the world has one or more symphony orchestras.

When I was young, I heard it said that only intellectuals could appreciate classical music, that it required dedicated concentration to appreciate. Nonsense. I'm no intellectual, and I've always loved classical music. Anyone who's ever seen and enjoyed Disney's Fantasia or a Looney Tunes cartoon playing Rossini's William Tell Overture or Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 can attest to the power and joy of classical music, and that's just about everybody.

So, if Classical Candor can expand one's awareness of classical music and bring more joy to one's life, more power to it. It's done its job. --John J. Puccio

Contact Information

Readers with polite, courteous, helpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@gmail.com

Readers with impolite, discourteous, bitchy, whining, complaining, nasty, mean-spirited, unhelpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@recycle.bin.