By Karl Nehring

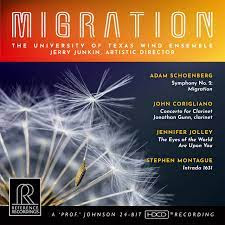

Adam Schoenberg: Symphony No. 2: Migration; John Corigliano: Concerto for Clarinet; Jennifer Jolley: The Eyes of the World are Upon You; Stephen Montague: Intrada 1631. Jonathan Gunn, clarinet; Brian Lewis, violin; The University of Texas Wind Ensemble, Jerry Junkin, Artistic Director. Reference Recordings RR-150

From the outset, the Reference Recordings label has enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for outstanding sound quality, and within the first few measures of Adam Schoenberg’s Symphony No. 2: Migration, it should be abundantly clear to most listeners that “Professor” Johnson has delivered yet again. A brass fanfare followed in quick order by some BIG bass drum whacks are impressive enough, but what really seals the deal, at least for those with woofers and/or subwoofers sufficient for the sound, is the deep rumbling resonant sound that lingers in the wake of the initial notes from the drum. Such a rare but sublime surprise it is to enjoy such a sound in your very own listeningspace! So yes, Migration can be counted as an audiophile release, but thank goodness, it is a release with substantial musical virtues as well. As you can see from the header above, this is music for wind ensemble, and the wind band from the University of Texas ranks as one of the very best in the world. No, we are not talking about a small wind ensemble as might perform chamber music, but rather a full-blown wind band comprising 60 or so members including woodwinds, brass, and percussion – something like an orchestra without the strings but with more sheer blowing power. Migration the composition was commissioned for the ensemble and dedicated to Jerry Junkin. It is in five relatively brief movements: I. March, II. Dreaming, III. Escape, IV. Crossing, V. Beginning. From the dramatic opening measures described above, the piece is a dramatic, lively, colorful, and entertaining symphony that bears repeated listening,

Next on the program is a work from a composer whose name is probably more familiar to our readers. Actually, however, the surname “Schoenberg” is quite likely more familiar than “Corigliano,” although the American composer of Migration, Adam Schoenberg (b 1981, is surely much less well-known than either the Austrian-American composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) or American composer John Corigliano (b. 1938), who originally wrote this piece for full symphony orchestra. According to the liner notes, “the original ‘Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra’ was written for Stanley Drucker, the first clarinetist of Corigliano’s youth, and was premiered on December 6, 1977 by the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein. Craig B. Davis created the wind ensemble version, and conducted its premiere on February 19, 2015 with Nicholas Councilor, clarinet, and The University of Texas Wind Ensemble.” The concerto consists of three movements: i: Cadenzas, II. Elegy, III. Antiphonal Toccata. Of special note is the second movement, Elegy, which is a deeply moving tribute to his father wherein the sound of the clarinet soloist is joined by the sound of a solo violin. Corigliano’s father served as concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic for 23 years. The outer movements feature more virtuosic and colorful playing, not just from Gunn on clarinet but the whole ensemble, but it is that second movement that is the emotional heart of the piece. The liner notes are adapted from Corigliano’s original program notes for that original New York Philharmonic performance, a nice touch from Reference Recordings.

| |

| UT Wind Ensemble |

Closing out the program is Intrada 1631 by the American composer and conductor Stephen Montague (b. 1943) who now lives in England. Montague writes of his 10-minute composition that it “was inspired by a concert of early South American liturgical music directed by Jeffery Skidmore at the Darlington Summer Music School in the summer of 2001. One of the most moving and memorable works in the program was a Hanacpachap cussicuinin, a 17th century Catholic liturgical chant written in Quechua, the native language of the Incas. The music was composed by a Franciscan missionary priest named Juan Pérez Bocanegra, who lived and worked in Cuzco (Peru), a small village east of Lima in the Jauja Valley during the early 17th century. Intrada 1631 uses Bocanegra’s twenty-bar hymn as the basis for an expanded processional scored for the modern forces of a symphonic brass choir with field drums.” The music is stately, formal, and powerful. What it lacks in tunefulness, it makes up for in solemnity and impact.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this review, Migration is an audiophile recording, not only for bass extension and dynamic impact, but also for the excellent sense of soundstage depth and width that it presents. How rewarding it is to have a true audiophile recording with genuine musical value; moreover, the liner notes are also excellent, with each of the composers commenting on their works, plus biographical information on the composers, soloists, and conductor as well as information about the University of Texas Wind Ensemble. The good folks at Reference Recordings have done themselves proud with this outstanding release.