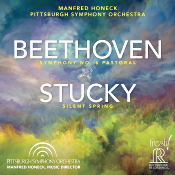

Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral” (SACD review)

Also, Stucky: Silent Spring. Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Reference Recordings FR-7475SACD.

By John J. Puccio

Beethoven wrote nine symphonies, at least five of which (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9) are probably the best known and most popular. But if I had to guess further, I’d say that today’s average non-classical music listener might only know the first four notes of the Fifth and the finale of the Ninth (oh, yeah, they’d say, that’s from Die-Hard). Yet thanks in part to Disney’s Fantasia, they might also recognize most any part of the Sixth. Which brings us to a dilemma faced by any conductor undertaking a new recording of the “Pastoral”: how to make it different enough to distinguish it from the 800 other recordings currently available and make it worthwhile enough for potential buyers to consider adding it to their music library.

Face it: There are already some great recordings of the Sixth Symphony from distinguished conductors like Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Karl Bohm, Otto Klemperer, Eugene Jochum, Jordi Savall, and many others. What would set Manfred Honeck’s rendition with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra apart from the rest? Well, certainly, Maestro Honeck chose a symphony with as great a variety of interpretations as any in the catalogue.

First, of course, there’s the matter Honeck discusses in the booklet notes. Should one approach the “Pastoral” as program or absolute, abstract music? He reasons that Beethoven gave us enough explanation of each movement that it is inevitable the composer meant for us to picture in our minds the scenes and events he’s describing. Honeck goes on to say, however, that there is a good deal of feeling in the music, Beethoven indicting in the score that the music should be played with “more sensation than painting.” So, one must not overlook the nuances of the score and create more than simply a cursory overview of the image. Honeck goes on in his extraordinarily thorough booklet notes to identify the various passages that he felt needed further clarification through extended contrasts or an emphasis on certain instruments.

Then there is the matter of tempos. Ah, yes, those tempos. Beethoven, it seems, fell in love with the newfangled metronome and added detailed tempo markings throughout his music. This was not to the liking of every conductor, as they preferred the broader Latin markings of Allegro, Andante, Largo, etc., which gave them more leeway in adopting a pace they preferred. An actual, specific tempo many of them felt was too restrictive. What’s more, just as many musical scholars believed (and some still believe) that Beethoven’s metronome may have been faulty because the speeds are so much more uniformly fast that most conductors were used to. Whatever, with the popular introduction of historically informed performance practice (HIP) and the period-instrument era of the mid-twentieth century, the adoption of Beethoven’s own tempo markings became more widespread. Ensembles like Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players, John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, and Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations among others helped put Beethoven’s own tempo markings back on the map. Still, these were period-instrument bands, and Honeck leads a modern-instrument one. Would he follow traditional big-orchestral practice or adopt Beethovent’s markings? It appears Honeck chose Beethoven. His timings for each of the Sixth Symphony’s movements are consistently as fast or even faster than Norrington, Gardiner, or Savall and clearly faster than most modern-orchestra recordings.

So, how does all of this work out for Maestro Honeck and the listener? That may depend of what you’re looking for in the work and, especially, what you’re used to. Let’s take the recording one movement at a time.

The first movement Beethoven marks as an Allegro ma non troppo (fast but not too fast) and calls it the “Arrival in the country.” Well, Honeck certainly got the “fast” part right, but the “not too fast” seems to elude him. Fortunately, the wide dynamcs and the dramatic pauses help to make the music vigorous and noteworthy. But I’m not sure an arrival in the country should be this hurried, despite the composer’s tempo marks.

The second movement is the “Scene at the brook,” marked Andante molto mosso (moderately fast). Traditionally, this would actually be a “slow” movement, but following Beethoven’s lead, Honeck again takes it rather briskly. Still, Honeck’s brook bubbles away in perfect harmony with Nature, and it appears as though the company of people at the stream are enjoying themselves.

The third movement Beethoven called the “Merry assembly of country folk” and labeled it an Allegro. Here, Honeck is clearly in his element. “It is said the peasants are revolting.” “You said it! They stink on ice!” --Mel Brooks, History of the World, Part I. The country folk do, indeed, appear to be having a good time.

The fifth movement, the “Thunderstorm,” Beethoven also labeled an Allegro. The storm is undoubtedly noisy, with the recording’s wide dynamics practically knocking you out of your chair. Honeck clearly achieves the impact the composer probably desired.

Then, the final movement is the “Shepherd's Song,” with the additional description “Benevolent feelings of thanksgiving to the deity after the storm.” Beethoven tags it an Allegretto (moderately fast but not so fast as an Allegro). Because the indicated tempos are significantly different from those we usually hear from modern orchestras, Honeck’s approach doesn’t seem fully to capture the merrymakers’ gratitude to the Lord at the passing of the thunder and lightning. It doesn’t project the exalted serenity we normally hear.

Now, whether my several qualms are justified, given Beethoven’s own intentions, or whether I am basing them on personal expectations due to years of listening to more conventional performances, I’m not sure. I do know that, for instance, I disliked Roger Norrington’s HIP approach of the Sixth, finding it rather antiseptic, but found Jordi Savall’s equally HIP approach totally delightful. All I can say about Honeck’s interpretation is that it may be a matter of acquired taste.

Coupled with the Beethoven is Steven Stucky’s Silent Spring, commissioned by and premiered in 2012 by Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Mr. Stucky (1949-2016) wrote his four-movement composition as a tribute to Rachel Carson’s best-selling 1962 wake-up call for environmentalism. Taking Carson’s own titles for the four movements, Stucky’s music reflects the themes of the book: “The Sea Around Us,” “The Lost Woods,” “Rivers of Death,” and “Silent Spring.” Honeck and the orchestra would seem to reflect these moods perfectly, and Stucky’s tone poem comes over as a wake-up call of its own.

Producer Dirk Sobotka and engineer Mark Donahue recorded the music live at Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts in June 2017 (Symphony No. 6) and April 2018 (Silent Spring). They recorded it for SACD 5.0 and 2-channel stereo playback as well as regular CD stereo, using five omnidirectional DPA 4006 microphones as the main array, supplemented by “spot mics” to clarify the detail of the orchestration. The recording itself was made in DSD256 and post-produced in DXD 352.8kHz/32 bit. I listened in SACD two-channel.

For a live recording, the sound of the Sixth is remarkably lifelike, meaning it’s not as close-up, bright, or one one-dimensional as are most live recordings. If anything, it’s a touch soft. Miked at a moderate distance, it sounds big and full, warm and natural. The wide dynamics help it seem even more realistic, although some listeners may object to the abrupt changes in playback levels. I enjoyed it. The sound of Silent Spring is more hi-fi oriented, a tad sharper and clearer and in-your-face.

JJP

John J. Puccio, Founder and Contributor

Understand, I'm just an everyday guy reacting to something I love. And I've been doing it for a very long time, my appreciation for classical music starting with the musical excerpts on the Big Jon and Sparkie radio show in the early Fifties and the purchase of my first recording, The 101 Strings Play the Classics, around 1956. In the late Sixties I began teaching high school English and Film Studies as well as becoming interested in hi-fi, my audio ambitions graduating me from a pair of AR-3 speakers to the Fulton J's recommended by The Stereophile's J. Gordon Holt. In the early Seventies, I began writing for a number of audio magazines, including Audio Excellence, Audio Forum, The Boston Audio Society Speaker, The American Record Guide, and from 1976 until 2008, The $ensible Sound, for which I served as Classical Music Editor.

Today, I'm retired from teaching and use a pair of bi-amped VMPS RM40s loudspeakers for my listening. In addition to writing for the Classical Candor blog, I served as the Movie Review Editor for the Web site Movie Metropolis (formerly DVDTown) from 1997-2013. Music and movies. Life couldn't be better.

Karl Nehring, Editor and Contributor

For nearly 30 years I was the editor of The $ensible Sound magazine and a regular contributor to both its equipment and recordings review pages. I would not presume to present myself as some sort of expert on music, but I have a deep love for and appreciation of many types of music, "classical" especially, and have listened to thousands of recordings over the years, many of which still line the walls of my listening room (and occasionally spill onto the furniture and floor, much to the chagrin of my long-suffering wife). I have always taken the approach as a reviewer that what I am trying to do is simply to point out to readers that I have come across a recording that I have found of interest, a recording that I think they might appreciate my having pointed out to them. I suppose that sounds a bit simple-minded, but I know I appreciate reading reviews by others that do the same for me — point out recordings that they think I might enjoy.

For readers who might be wondering about what kind of system I am using to do my listening, I should probably point out that I do a LOT of music listening and employ a variety of means to do so in a variety of environments, as I would imagine many music lovers also do. Starting at the more grandiose end of the scale, the system in which I do my most serious listening comprises Marantz CD 6007 and Onkyo CD 7030 CD players, NAD C 658 streaming preamp/DAC, Legacy Audio PowerBloc2 amplifier, and a pair of Legacy Audio Focus SE loudspeakers. I occasionally do some listening through pair of Sennheiser 560S headphones. I miss the excellent ELS Studio sound system in our 2016 Acura RDX (now my wife's daily driver) on which I had ripped more than a hundred favorite CDs to the hard drive, so now when driving my 2024 Honda CRV Sport L Hybrid, I stream music from my phone through its adequate but hardly outstanding factory system. For more casual listening at home when I am not in my listening room, I often stream music through a Roku Streambar Pro system (soundbar plus four surround speakers and a 10" sealed subwoofer) that has surprisingly nice sound for such a diminutive physical presence and reasonable price. Finally, at the least grandiose end of the scale, I have an Ultimate Ears Wonderboom II Bluetooth speaker and a pair of Google Pro Earbuds for those occasions where I am somewhere by myself without a sound system but in desperate need of a musical fix. I just can’t imagine life without music and I am humbly grateful for the technologies that enable us to enjoy it in so many wonderful ways.

William (Bill) Heck, Webmaster and Contributor

Among my early childhood memories are those of listening to my mother playing records (some even 78 rpm ones!) of both classical music and jazz tunes. I suppose that her love of music was transmitted genetically, and my interest was sustained by years of playing in rock bands – until I realized that this was no way to make a living. The interest in classical music was rekindled in grad school when the university FM station serving as background music for studying happened to play the Brahms First Symphony. As the work came to an end, it struck me forcibly that this was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard, and from that point on, I never looked back. This revelation was to the detriment of my studies, as I subsequently spent way too much time simply listening, but music has remained a significant part of my life. These days, although I still can tell a trumpet from a bassoon and a quarter note from a treble clef, I have to admit that I remain a nonexpert. But I do love music in general and classical music in particular, and I enjoy sharing both information and opinions about it.

The audiophile bug bit about the same time that I returned to classical music. I’ve gone through plenty of equipment, brands from Audio Research to Yamaha, and the best of it has opened new audio insights. Along the way, I reviewed components, and occasionally recordings, for The $ensible Sound magazine. Most recently I’ve moved to my “ultimate system” consisting of a BlueSound Node streamer, an ancient Toshiba multi-format disk player serving as a CD transport, Legacy Wavelet II DAC/preamp/crossover, dual Legacy PowerBloc2 amps, and Legacy Signature SE speakers (biamped), all connected with decently made, no-frills cables. With the arrival of CD and higher resolution streaming, that is now the source for most of my listening.

Ryan Ross, Contributor

I started listening to and studying classical music in earnest nearly three decades ago. This interest grew naturally out of my training as a pianist. I am now a musicologist by profession, specializing in British and other symphonic music of the 19th and 20th centuries. My scholarly work has been published in major music journals, as well as in other outlets. Current research focuses include twentieth-century symphonic historiography, and the music of Jean Sibelius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Malcolm Arnold.

I am honored to contribute writings to Classical Candor. In an age where the classical recording industry is being subjected to such profound pressures and changes, it is more important than ever for those of us steeped in this cultural tradition to continue to foster its love and exposure. I hope that my readers can find value, no matter how modest, in what I offer here.

Bryan Geyer, Technical Analyst

I initially embraced classical music in 1954 when I mistuned my car radio and heard the Heifetz recording of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto. That inspired me to board the new "hi-fi" DIY bandwagon. In 1957 I joined one of the pioneer semiconductor makers and spent the next 32 years marketing transistors and microcircuits to military contractors. Home audio DIY projects remained a personal passion until 1989 when we created our own new photography equipment company. I later (2012) revived my interest in two channel audio when we "downsized" our life and determined that mini-monitors + paired subwoofers were a great way to mate fine music with the space constraints of condo living.

Visitors that view my technical papers on this site may wonder why they appear here, rather than on a site that features audio equipment reviews. My reason is that I tried the latter, and prefer to publish for people who actually want to listen to music; not to equipment. My focus is in describing what's technically beneficial to assure that the sound of the system will accurately replicate the source input signal (i. e. exhibit high accuracy) without inordinate cost and complexity. Conversely, most of the audiophiles of today strive to achieve sound that's euphonic, i.e. be personally satisfying. In essence, audiophiles seek sound that's consistent with their desire; the music is simply a test signal.

Mission Statement

It is the goal of Classical Candor to promote the enjoyment of classical music. Other forms of music come and go--minuets, waltzes, ragtime, blues, jazz, bebop, country-western, rock-'n'-roll, heavy metal, rap, and the rest--but classical music has been around for hundreds of years and will continue to be around for hundreds more. It's no accident that every major city in the world has one or more symphony orchestras.

When I was young, I heard it said that only intellectuals could appreciate classical music, that it required dedicated concentration to appreciate. Nonsense. I'm no intellectual, and I've always loved classical music. Anyone who's ever seen and enjoyed Disney's Fantasia or a Looney Tunes cartoon playing Rossini's William Tell Overture or Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 can attest to the power and joy of classical music, and that's just about everybody.

So, if Classical Candor can expand one's awareness of classical music and bring more joy to one's life, more power to it. It's done its job. --John J. Puccio

Contact Information

Readers with polite, courteous, helpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@gmail.com

Readers with impolite, discourteous, bitchy, whining, complaining, nasty, mean-spirited, unhelpful letters may send them to classicalcandor@recycle.bin.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment. It will be published after review.