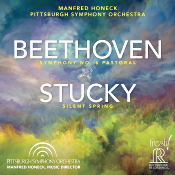

Also, Stucky: Silent Spring. Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Reference Recordings FR-7475SACD.

By John J. Puccio

Beethoven wrote nine symphonies, at least five of which (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9) are probably the best known and most popular. But if I had to guess further, I’d say that today’s average non-classical music listener might only know the first four notes of the Fifth and the finale of the Ninth (oh, yeah, they’d say, that’s from Die-Hard). Yet thanks in part to Disney’s Fantasia, they might also recognize most any part of the Sixth. Which brings us to a dilemma faced by any conductor undertaking a new recording of the “Pastoral”: how to make it different enough to distinguish it from the 800 other recordings currently available and make it worthwhile enough for potential buyers to consider adding it to their music library.

Face it: There are already some great recordings of the Sixth Symphony from distinguished conductors like Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Karl Bohm, Otto Klemperer, Eugene Jochum, Jordi Savall, and many others. What would set Manfred Honeck’s rendition with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra apart from the rest? Well, certainly, Maestro Honeck chose a symphony with as great a variety of interpretations as any in the catalogue.

First, of course, there’s the matter Honeck discusses in the booklet notes. Should one approach the “Pastoral” as program or absolute, abstract music? He reasons that Beethoven gave us enough explanation of each movement that it is inevitable the composer meant for us to picture in our minds the scenes and events he’s describing. Honeck goes on to say, however, that there is a good deal of feeling in the music, Beethoven indicting in the score that the music should be played with “more sensation than painting.” So, one must not overlook the nuances of the score and create more than simply a cursory overview of the image. Honeck goes on in his extraordinarily thorough booklet notes to identify the various passages that he felt needed further clarification through extended contrasts or an emphasis on certain instruments.

Then there is the matter of tempos. Ah, yes, those tempos. Beethoven, it seems, fell in love with the newfangled metronome and added detailed tempo markings throughout his music. This was not to the liking of every conductor, as they preferred the broader Latin markings of Allegro, Andante, Largo, etc., which gave them more leeway in adopting a pace they preferred. An actual, specific tempo many of them felt was too restrictive. What’s more, just as many musical scholars believed (and some still believe) that Beethoven’s metronome may have been faulty because the speeds are so much more uniformly fast that most conductors were used to. Whatever, with the popular introduction of historically informed performance practice (HIP) and the period-instrument era of the mid-twentieth century, the adoption of Beethoven’s own tempo markings became more widespread. Ensembles like Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players, John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, and Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations among others helped put Beethoven’s own tempo markings back on the map. Still, these were period-instrument bands, and Honeck leads a modern-instrument one. Would he follow traditional big-orchestral practice or adopt Beethovent’s markings? It appears Honeck chose Beethoven. His timings for each of the Sixth Symphony’s movements are consistently as fast or even faster than Norrington, Gardiner, or Savall and clearly faster than most modern-orchestra recordings.

So, how does all of this work out for Maestro Honeck and the listener? That may depend of what you’re looking for in the work and, especially, what you’re used to. Let’s take the recording one movement at a time.

The first movement Beethoven marks as an Allegro ma non troppo (fast but not too fast) and calls it the “Arrival in the country.” Well, Honeck certainly got the “fast” part right, but the “not too fast” seems to elude him. Fortunately, the wide dynamcs and the dramatic pauses help to make the music vigorous and noteworthy. But I’m not sure an arrival in the country should be this hurried, despite the composer’s tempo marks.

The second movement is the “Scene at the brook,” marked Andante molto mosso (moderately fast). Traditionally, this would actually be a “slow” movement, but following Beethoven’s lead, Honeck again takes it rather briskly. Still, Honeck’s brook bubbles away in perfect harmony with Nature, and it appears as though the company of people at the stream are enjoying themselves.

The third movement Beethoven called the “Merry assembly of country folk” and labeled it an Allegro. Here, Honeck is clearly in his element. “It is said the peasants are revolting.” “You said it! They stink on ice!” --Mel Brooks, History of the World, Part I. The country folk do, indeed, appear to be having a good time.

The fifth movement, the “Thunderstorm,” Beethoven also labeled an Allegro. The storm is undoubtedly noisy, with the recording’s wide dynamics practically knocking you out of your chair. Honeck clearly achieves the impact the composer probably desired.

Then, the final movement is the “Shepherd's Song,” with the additional description “Benevolent feelings of thanksgiving to the deity after the storm.” Beethoven tags it an Allegretto (moderately fast but not so fast as an Allegro). Because the indicated tempos are significantly different from those we usually hear from modern orchestras, Honeck’s approach doesn’t seem fully to capture the merrymakers’ gratitude to the Lord at the passing of the thunder and lightning. It doesn’t project the exalted serenity we normally hear.

Now, whether my several qualms are justified, given Beethoven’s own intentions, or whether I am basing them on personal expectations due to years of listening to more conventional performances, I’m not sure. I do know that, for instance, I disliked Roger Norrington’s HIP approach of the Sixth, finding it rather antiseptic, but found Jordi Savall’s equally HIP approach totally delightful. All I can say about Honeck’s interpretation is that it may be a matter of acquired taste.

Coupled with the Beethoven is Steven Stucky’s Silent Spring, commissioned by and premiered in 2012 by Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Mr. Stucky (1949-2016) wrote his four-movement composition as a tribute to Rachel Carson’s best-selling 1962 wake-up call for environmentalism. Taking Carson’s own titles for the four movements, Stucky’s music reflects the themes of the book: “The Sea Around Us,” “The Lost Woods,” “Rivers of Death,” and “Silent Spring.” Honeck and the orchestra would seem to reflect these moods perfectly, and Stucky’s tone poem comes over as a wake-up call of its own.

Producer Dirk Sobotka and engineer Mark Donahue recorded the music live at Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts in June 2017 (Symphony No. 6) and April 2018 (Silent Spring). They recorded it for SACD 5.0 and 2-channel stereo playback as well as regular CD stereo, using five omnidirectional DPA 4006 microphones as the main array, supplemented by “spot mics” to clarify the detail of the orchestration. The recording itself was made in DSD256 and post-produced in DXD 352.8kHz/32 bit. I listened in SACD two-channel.

For a live recording, the sound of the Sixth is remarkably lifelike, meaning it’s not as close-up, bright, or one one-dimensional as are most live recordings. If anything, it’s a touch soft. Miked at a moderate distance, it sounds big and full, warm and natural. The wide dynamics help it seem even more realistic, although some listeners may object to the abrupt changes in playback levels. I enjoyed it. The sound of Silent Spring is more hi-fi oriented, a tad sharper and clearer and in-your-face.

JJP

By John J. Puccio

Beethoven wrote nine symphonies, at least five of which (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9) are probably the best known and most popular. But if I had to guess further, I’d say that today’s average non-classical music listener might only know the first four notes of the Fifth and the finale of the Ninth (oh, yeah, they’d say, that’s from Die-Hard). Yet thanks in part to Disney’s Fantasia, they might also recognize most any part of the Sixth. Which brings us to a dilemma faced by any conductor undertaking a new recording of the “Pastoral”: how to make it different enough to distinguish it from the 800 other recordings currently available and make it worthwhile enough for potential buyers to consider adding it to their music library.

Face it: There are already some great recordings of the Sixth Symphony from distinguished conductors like Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Karl Bohm, Otto Klemperer, Eugene Jochum, Jordi Savall, and many others. What would set Manfred Honeck’s rendition with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra apart from the rest? Well, certainly, Maestro Honeck chose a symphony with as great a variety of interpretations as any in the catalogue.

First, of course, there’s the matter Honeck discusses in the booklet notes. Should one approach the “Pastoral” as program or absolute, abstract music? He reasons that Beethoven gave us enough explanation of each movement that it is inevitable the composer meant for us to picture in our minds the scenes and events he’s describing. Honeck goes on to say, however, that there is a good deal of feeling in the music, Beethoven indicting in the score that the music should be played with “more sensation than painting.” So, one must not overlook the nuances of the score and create more than simply a cursory overview of the image. Honeck goes on in his extraordinarily thorough booklet notes to identify the various passages that he felt needed further clarification through extended contrasts or an emphasis on certain instruments.

Then there is the matter of tempos. Ah, yes, those tempos. Beethoven, it seems, fell in love with the newfangled metronome and added detailed tempo markings throughout his music. This was not to the liking of every conductor, as they preferred the broader Latin markings of Allegro, Andante, Largo, etc., which gave them more leeway in adopting a pace they preferred. An actual, specific tempo many of them felt was too restrictive. What’s more, just as many musical scholars believed (and some still believe) that Beethoven’s metronome may have been faulty because the speeds are so much more uniformly fast that most conductors were used to. Whatever, with the popular introduction of historically informed performance practice (HIP) and the period-instrument era of the mid-twentieth century, the adoption of Beethoven’s own tempo markings became more widespread. Ensembles like Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players, John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, and Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations among others helped put Beethoven’s own tempo markings back on the map. Still, these were period-instrument bands, and Honeck leads a modern-instrument one. Would he follow traditional big-orchestral practice or adopt Beethovent’s markings? It appears Honeck chose Beethoven. His timings for each of the Sixth Symphony’s movements are consistently as fast or even faster than Norrington, Gardiner, or Savall and clearly faster than most modern-orchestra recordings.

So, how does all of this work out for Maestro Honeck and the listener? That may depend of what you’re looking for in the work and, especially, what you’re used to. Let’s take the recording one movement at a time.

The first movement Beethoven marks as an Allegro ma non troppo (fast but not too fast) and calls it the “Arrival in the country.” Well, Honeck certainly got the “fast” part right, but the “not too fast” seems to elude him. Fortunately, the wide dynamcs and the dramatic pauses help to make the music vigorous and noteworthy. But I’m not sure an arrival in the country should be this hurried, despite the composer’s tempo marks.

The second movement is the “Scene at the brook,” marked Andante molto mosso (moderately fast). Traditionally, this would actually be a “slow” movement, but following Beethoven’s lead, Honeck again takes it rather briskly. Still, Honeck’s brook bubbles away in perfect harmony with Nature, and it appears as though the company of people at the stream are enjoying themselves.

The third movement Beethoven called the “Merry assembly of country folk” and labeled it an Allegro. Here, Honeck is clearly in his element. “It is said the peasants are revolting.” “You said it! They stink on ice!” --Mel Brooks, History of the World, Part I. The country folk do, indeed, appear to be having a good time.

The fifth movement, the “Thunderstorm,” Beethoven also labeled an Allegro. The storm is undoubtedly noisy, with the recording’s wide dynamics practically knocking you out of your chair. Honeck clearly achieves the impact the composer probably desired.

Then, the final movement is the “Shepherd's Song,” with the additional description “Benevolent feelings of thanksgiving to the deity after the storm.” Beethoven tags it an Allegretto (moderately fast but not so fast as an Allegro). Because the indicated tempos are significantly different from those we usually hear from modern orchestras, Honeck’s approach doesn’t seem fully to capture the merrymakers’ gratitude to the Lord at the passing of the thunder and lightning. It doesn’t project the exalted serenity we normally hear.

Now, whether my several qualms are justified, given Beethoven’s own intentions, or whether I am basing them on personal expectations due to years of listening to more conventional performances, I’m not sure. I do know that, for instance, I disliked Roger Norrington’s HIP approach of the Sixth, finding it rather antiseptic, but found Jordi Savall’s equally HIP approach totally delightful. All I can say about Honeck’s interpretation is that it may be a matter of acquired taste.

Coupled with the Beethoven is Steven Stucky’s Silent Spring, commissioned by and premiered in 2012 by Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Mr. Stucky (1949-2016) wrote his four-movement composition as a tribute to Rachel Carson’s best-selling 1962 wake-up call for environmentalism. Taking Carson’s own titles for the four movements, Stucky’s music reflects the themes of the book: “The Sea Around Us,” “The Lost Woods,” “Rivers of Death,” and “Silent Spring.” Honeck and the orchestra would seem to reflect these moods perfectly, and Stucky’s tone poem comes over as a wake-up call of its own.

Producer Dirk Sobotka and engineer Mark Donahue recorded the music live at Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts in June 2017 (Symphony No. 6) and April 2018 (Silent Spring). They recorded it for SACD 5.0 and 2-channel stereo playback as well as regular CD stereo, using five omnidirectional DPA 4006 microphones as the main array, supplemented by “spot mics” to clarify the detail of the orchestration. The recording itself was made in DSD256 and post-produced in DXD 352.8kHz/32 bit. I listened in SACD two-channel.

For a live recording, the sound of the Sixth is remarkably lifelike, meaning it’s not as close-up, bright, or one one-dimensional as are most live recordings. If anything, it’s a touch soft. Miked at a moderate distance, it sounds big and full, warm and natural. The wide dynamics help it seem even more realistic, although some listeners may object to the abrupt changes in playback levels. I enjoyed it. The sound of Silent Spring is more hi-fi oriented, a tad sharper and clearer and in-your-face.

JJP

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment. It will be published after review.